The impact of communication anxiety regulation and fear of missing out on social media dependency: a study on transgender individuals in Turkey

Article information

Abstract

The current study aims to explore the impact of communication anxiety regulation and the fear of missing out on social media dependency, by specifically focusing on transgender individuals living in Turkey. Even though sexual orientation is not outlawed and legal sex change has been possible since 1988, Turkey stands as one of the most restrictive countries in Europe, when it comes to LGBT+ rights. In that sense, transgender individuals experience various social, political, and economic challenges throughout their lives, which have the potential to shape their relations with social media. Findings suggest that dimensions of communication anxiety regulation and fear of missing out determine social media dependency. Future studies should explore whether intense social media use as a result of communication anxiety and fear of missing out encourage productive activities such as interactive community support, self-help, and information seeking.

Introduction

Transgender individualsi, who have a gender identity that differs from the one that is assigned at birth, experience various challenges in their social, economic, and political life. Looking on the bright side, one can state that recognition of transgender individuals is higher than ever thanks to the rising visibility, unprecedented advocacy, and changing public opinion (Movement Advancement Project, 2016). The Internet, and specifically social media, play a key role in terms of increasing the visibility of transgender people, thanks to users’ content creations on platforms such as YouTube, Reddit, Tumblr, TikTok and Instagram. However, this visibility also has brought along new challenges such as backlashes from religious and politically conservative communities, and online harassment towards transgender content creators who receive considerable public attention (Burns, 2019).

In contrast to the increasing visibility and recognition, it is not possible to legally change your gender at least in 47 United Nations member states (Lopez & Weerawardhana, 2021). While 96 countries describe processes for gender change on a legal basis, only 25 of them do not have any prohibitive requirements (Lopez & Weerawardhana, 2021). Besides the physical and psychological challenges transgender individuals go through, they are also expected to deal with legal and social obstacles in restrictive countries.

Turkey ranks 54th among 189 countries in terms of gender equality on United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Index, following two decades of relatively steady progress. However, on Gender Development Index, Turkey remains at a much lower position (68th among 162 countries), besides ranking the lowest among OECD countries (UNDP Türkiye, 2022). The existing data remain scant, since today one’s own sense of gender can be reflected in more than two ways. For example, transgender is regarded as an umbrella term, that does not only refer to people whose gender identity is the opposite of their assigned sex, but also includes individuals who identify as queer or non-binary. Current data on gender equality in Turkey reflects the comparison among cisgender individuals and neglects nonconformist gender identities, gathered under the category of transgender. In line, the population data gathered and composed by the Turkish Statistical Institute in 2022 reflects male/female division in Turkey’s society, in which men compose 50.1 % with 42.428.101 individuals and women compose 49.9 with 42.252.172 individuals (Turkish Statistical Institute, 2022).

Previous studies on the social media use of LGBT+ focus on health information seeking (Adkins et al., 2018) and the impact of social media use on risky sexual behavior intentions (Hirshfield et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2016). An interesting finding is noted by Nazzal et al. (2018) and Wright et al. (2017), who state that the excessive use of social media can be deteriorating for offline mental health among LGBT+. The current study extends the existing literature by specifically focusing on transgender individuals and the factors that have the potential to determine social media dependency. Since LGBTQ+ is a broad abbreviation that refers to individuals with various gender identities and/or sexual orientations, the current study solely focuses on transgender individuals, in order to provide specific insights related to transgender communities. In line, the snowball sampling technique was applied during the data collection process to reach transgender individuals based in İstanbul, Turkey, to assess potential causal relationships between communication anxiety regulation, fear of missing out, and social media dependency.

Literature Review

Social media dependency

The social media dependency (SMD) approach borrows its roots from the media system dependency (MSD) theory. MSD approach, which is proposed by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur in 1976, aims to describe the contingent impacts of the mass media on receptors (Ball-Rokeach, 1985; 1998). The dependency phrase refers to the two-way relationships between media, social systems, and individuals. According to MSD theory, the more the media meets the demands of individuals, the more individuals would be dependent on the media (Yang et al., 2015). The media can exert more impact on individuals as a consequence of this process. When one considers how social media have evolved since the era of web 2.0 in terms of customization and personalization, it can be argued that SMD may be the case with a considerable number of Internet users. Thus, the study of MSD needs to be extended into the realm of social media.

There is no strict definition of which individuals can be considered as social media dependent. In other words, there is no concise amount of time spent on social media that is defined as social media dependency. A similar situation is the case with social media addiction. A relativistic approach should be embraced such as building or adapting a scale on social media use while understanding individuals’ relation with the online world. Still, it must be noted that previous research argues that individuals who spend more than 5 hours online are twice more likely to suffer from depression. Moreover, social media dependent individuals are noted to spend up to 9 hours online (Jenner, 2015).

Kim and Jung (2016) explain SMD as the degree of the helpfulness of social media for fulfilling a variety of important goals in everyday life. In this sense, SMD differs from the social media addiction (SMA) approach, which is a behavioral situation that is marked by being overly concerned about social media, driven by an uncontrollable need to log in and use online social networks in a degree, that significantly impairs other important areas of life. SMA differentiates itself from SMD, and even, FOMO, in the sense that it refers to a radical situation just like any other addiction experience.

Though limited, there are a variety of studies that study the SMD approach from different perspectives. The study of Kim and Jung (2017), which examine the potential relationship between SMD and interpersonal storytelling, explains that SMD has a direct impact on individuals’ level of engagement with interactive activities on social media. In another research, Yang et al. (2015) reveal that SMD is a significant predictor of online content purchases. In the context of LGBT+, Han et al. (2019) conduct an online survey of 1391 LGBT+ individuals and find out that LGBT+ individuals with higher levels of depression and dis-identification are more likely to be dependent on social media. Additionally, researchers point out that LGBT+ who have a longer history with social media are less dependent on social media, and have better offline psychological well-being. Just as depression and self dis-identification, many other critical factors may lead to SMD-related behavior among LGBT+. These potential factors include skills and competency in with dealing with communication anxiety and FOMO inclination. In line, this study aims to assess potential relationships between SMD and communication anxiety regulation, and SMD and FOMO.

Communication anxiety

Anxiety is typically perceived as emotional and/or psychological arousal marked by feelings of worry and dread (Fitch et al., 2011). Barlow (2002) defines anxiety as a “future-oriented mood state in which one is ready or prepared to attempt to cope with upcoming negative events” (p. 1247). Besides emotional symptoms such as avoidance, forgetfulness, and confusion, signs of anxiety may show up with physical symptoms such as dizziness, muscle tension, restlessness, and headaches (Seligman, 1998).

Communication anxiety is defined as the fear individuals encounter as they anticipate or engage in a communication event (Hanley White, et al., 2015). Hanley White et al. (2015) argue that it is important for communication researchers to assess how individuals react in various communication settings when they are in a state of anxiety. Regulation plays a key role in this process, in terms of evaluating individuals’ skills in coping and managing with anxiety.

Communication anxiety is studied in various settings such as instructional communication (e.g., McCroskey & Sheahan, 1978; Su, 2021; Wombacher et al., 2017), public speaking (e.g., Ayres, 1985; Finn, Sawyer & Behnke, 2009; Fitch et al., 2011), mood management during media consumption (e.g., Zillmann, 1988; Zillmann & Bryant, 1985), health communication (Zhao et al., 2021) and organizational communication (Fuller et al., 2016). So far, there are only a few studies that treat communication anxiety from the perspective of regulation.

The primary study on communication anxiety regulation is conducted by Hanley White et al. (2015), who argue that developing a scale on anxiety regulation may potentially help professionals while diagnosing and treating communication anxiety. Despite the existence of previous related scales, such as the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) developed by Gross and John (2003), and Carver et al.’s (1989) self-report measure of coping strategies (COPE), Communication Anxiety Regulation Scale (CARS) aims to specifically assess individuals’ anxiety management capability during their stressful communicative experiences. Basing her study on the scale developed by Hanley White et al. (2015), Shue (2020) identifies four broad strategies for regulating communication anxiety: “cognitive reappraisal (changing one’s mindset), avoidance (not thinking about the anxiety or thinking of something else), suppression (not expressing the anxiety), and venting (expressing the anxiety or unburdening oneself)” (p. 212).

This approach remains relevant and essential for studying transgender identity from a communications perspective when one considers the fact that transgender individuals engage in various social communicative environments such as home (i.e., Norwood, 2015) and workplace (i.e., Jones, 2020) that have the potential to create the feeling of anxiousness, related with minority stress.

H1: There is a significant relationship between venting and social media dependency.

H2: There is a significant relationship between suppression and social media dependency.

H3: There is a significant relationship between avoidance and social media dependency.

H4: There is a significant relationship between reappraisal and social media dependency.

Fear of missing out (FOMO)

Content FOMO is a term that refers to the occurrence of anxiety states in times when it is impossible to engage in the social sphere mainly via electronic tools of communication (Hetz et al., 2015). The term is related to a continuous demand to be connected with social media and its users, to share updates about one’s activities as well as to receive updates from others. The underlying reason for FOMO is the belief that one might be missing rewarding experiences when they are absent from spheres of electronic communication.

Though FOMO is mainly associated with forms of electronic communication today, it is developed as a more extensive concept in the mid-1990s by Dan Herman (Wortham, 2011). Following a series of customer interviews, Herman stated that FOMO is “a clearly fearful attitude towards the possibility of failing to exhaust available opportunities and missing the expected joy associated with succeeding in doing so”. Following Przybylski et al.’s (2013) consideration of FOMO in the context of social media, the concept is treated as an element of new media studies.

Studies on FOMO have so far shown that this condition emerges when one experiences failure while meeting the psychological need for belonging (Przybylski et al., 2013). Excessive engagement in social media may distract individuals from critical social experiences in the offline world and lead them to being part of a vicious circle of escape (Turkle, 2017). The underlying motivation behind this need for escape can be related to negative moods, depression and limited satisfaction with life (Ellison et al., 2007).

Previous research explores FOMO from various perspectives. For example, Przybylski et al. (2013) explain that FOMO serves as an intermediary factor between psychological variables and social media engagement, while the study by Koban et al. (2002) reveals that COVID information FOMO during the COVID-19 pandemic contributes to daytime tiredness. In another study, Alabri (2002) states that the need to belong is the primary factor that leads to FOMO on social media, while Hunt et al. (2018) argue that limiting social media use decreases FOMO and feelings of loneliness, as well as the occurrence of depression. A study with contrasting findings is conducted by Roberts and David (2020), which points to a positive outcome of FOMO. The study explains that FOMO can have a positive impact on the well-being of an individual, if it leads to social media use that supports social connection and engagement. In that sense, Roberts and David’s (2020) study remains unique in terms of proving that FOMO does not necessarily lead to negative behaviors or outcomes. Especially in the context of marginalized and/or underrepresented communities such as transgender individuals, FOMO may result in the creation of social bonds via social media and the creation of a communal feeling. The opposite can also be the case by isolating individuals from the outside world and creating an abstract sphere where individuals do not have any physical or social connection. In that sense, it is worth exploring FOMO in terms of its relation to social media dependency.

H5: There is a significant relationship between social media dependency and FOMO.

The study context: Being transgender in Turkey

Transgender identities are recognized in Turkey’s constitution, in the context of gender transition. In other words, the current legal recognition only embraces transsexual individuals, who desire to permanently transition to the sex or gender with which they identify, through hormone replacement therapy and sex reassignment surgery. The gender transition process is defined in the Article 40 of Turkish Civil Code under the title “Sex Change” (Türk Medeni Kanunu, 2001).

According to the code, an individual who desires to change their gender can apply in person and may request the court to permit the sex change process. An applicant is expected to be aged 18 or above and to be single in terms of marital status. Medical reports are requested which are to be received from governmental education and research hospitals, that question whether sex change is a bare necessity for the applicant’s mental health status. In other words, an individual who identifies as transgender and desires sex change must prove to government officials their struggle with gender dysphoria with requested medical reports.

Turkey’s transgender community has experienced various ups and downs since the 1980s. Bülent Ersoy, a Turkish transsexual singer, referred to as the diva of Turkish classical music, became the forerunner of social progress. Following the military coup d’état in 1980, Ersoy was banned from performing on stage alongside with other and relatively less known transsexual and gay singers, located in Turkey. At the height of her career, Ersoy lived in Germany and Australia, and returned back to İstanbul in the late 1980s, when she was granted her new national ID card as a woman and the opportunity to return back to the stage (Arslanbezer, 2021).

Despite Bülent Ersoy obtains royal status in Turkey’s society due to her outstanding vocal skills and artistic contributions, it is not easy for an ordinary transgender individual to engage in everyday life. Şahika Yüksel, a pioneer psychologist in sexual education, treatment, and research, explains in one of her interviews that many Turkish parents do not accept when their children come out as transgender, but they can appreciate someone who is a figure outside, such as a media personality. This situation is statistically proved by the findings of KONDA Research Company, which explain that the percentage of people who do not want to be neighbors with an LGBT+ individual has risen from 51,9 % to 57,2 % between 2017 and 2020 (Erem, 2021). Thus, the majority of transgender individuals, especially transgender women, who do not have access to financial resources and education are pushed to the peripheries of Turkey’s society, ghetto neighborhoods and are forced to engage in sex work. This situation is a good example of Durkheim’s (1895) social stigma theory - which was also later revisited by Goffman (1963) - that refers to the classification of a person as undesirable and be subject to societal stereotypes. It can be stated that transgender identities are stigmatized in Turkey; allowed to exist in limited social and/or mediated spheres, and mainly distant from the center of Turkey’s society.

Methodology and Measures

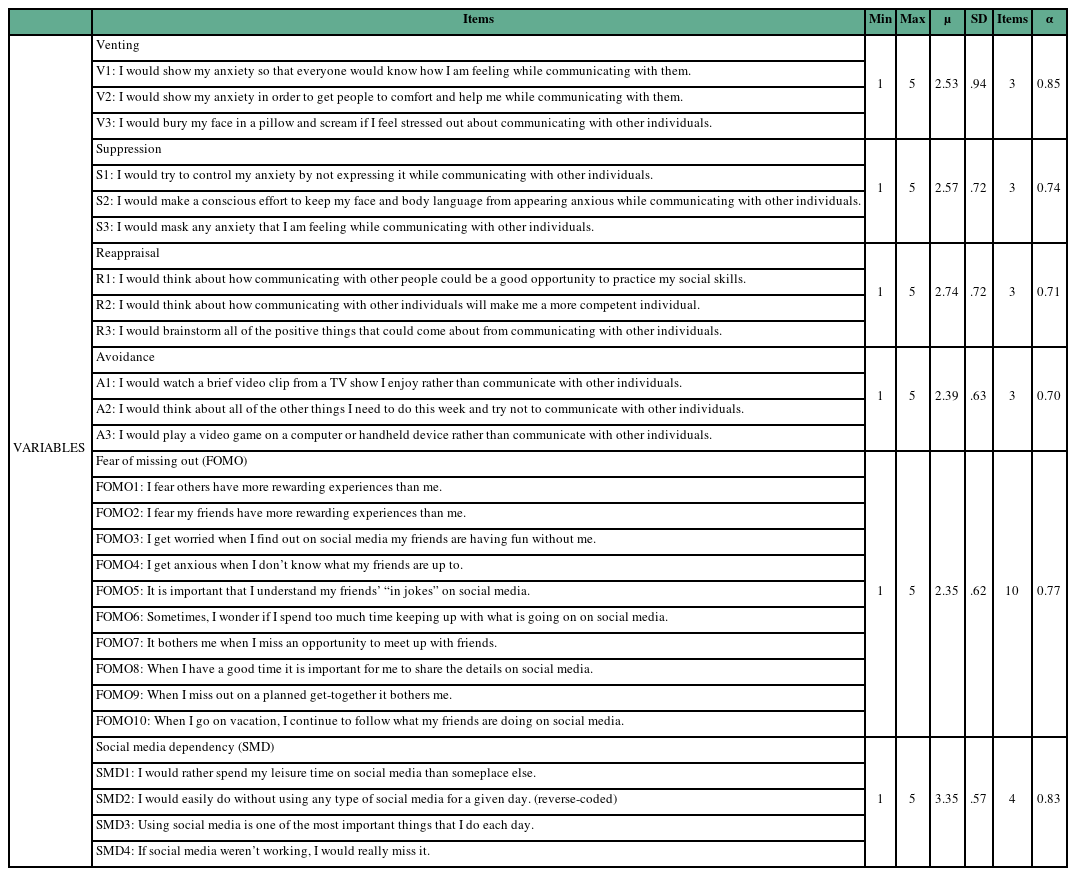

The structured scales are built on construct items of communication anxiety regulation, fear of missing out, and social media dependency. For the current study, the 12-item communication anxiety regulation scale (CARS) is adapted from the study of Shue (2020), while the 10-item fear of missing out (FOMO) scale is adopted from Bowman and Clark-Gordon (2020) (e.g., “I get anxious when I don’t know what my friends are up to”.). Based upon the results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), 3 items on “reappraisal”, 3 items on “avoidance”, 3 items on “suppression” and 3 items on “venting” are loaded in line with the original CARS scale. The 4-item social media dependency (SMD) scale is borrowed from the work of Tang and Mahoney (2020) and included items such as “I would rather spend my leisure time on social media than someplace else” and “If the social media were not working, I would really miss it”. All scaled questions are asked through the use of the 5-point Likert scale (1: Totally Disagree, 5: Totally Agree) except for questions on demographics.

The survey instrument is pilot tested with the voluntary participation of 25 individuals before the actual data collection process. A total of 324 respondents took part in the survey study. The survey data was collected between January 01-March 01 2022, in İstanbul, Turkey, by utilizing the snowball sampling method. Snowball sampling is one of the most effective methods for reaching segments of society, who might have a higher potential to request to be unrecorded for the fear of being stigmatized (Parker, 2019).

The process started by reaching out to a volunteer LGBT+ individual who is an active member of the SPOD non-governmental organization based in İstanbul, which aims to provide legal, social and psycho-social support for LGBT+ community. The volunteer participant (the seed) is then asked to recommend other contacts who fit the study criteria. The study criteria were designated as reaching 18+ LGBT+ individuals, who reside in İstanbul, Turkey, and using social media. The same procedure is conducted until compiling the overall dataset. Following the removal of surveys with missing data, 299 participants remained in the main analysis. All participants are aged 18 and older and the average age of the participants is 27.

The dataset is analyzed by using the latest version of SPSS software (SPSS 28). A cross-sectional design is employed that contains several self-report measures. After the coding procedure, the data on demographics and social media use are obtained with frequency analysis.

The reliability estimates are obtained for each of the construct domains. Cronbach’s α values range from 0.70 to 0.85 for each construct. To assess potential relationships, the independent and dependent variables are entered into multiple regression analysis, following the correlation analysis.

Findings

All participants identified themselves as transgender. The majority of participants are bachelor’s degree holders (61.6 %), who are followed by high school degree holders (17.8 %), graduate degree holders (7.2 %), primary school holders (4%), and middle school degree holders (9.4 %). 24% of participants state their monthly income is between 10.000-20.000 TL (550-1100 USD), while 70% of participants receive a salary/income below 10.000 TL (550 USD). 6% of participants explain their monthly income is or above 20.000 TL (1100 USD).

Participants spend more than 3 hours on social media on a daily basis. 54.27% participants state they spend more than 6 hours on social media on a regular day. The most frequently visited social platforms are TikTok (78.2%), followed by Instagram (64.3%), Twitter (43.3%), Facebook (27.2%) and Tinder (26.4%). Smartphones remain as the most preferred tool to engage with social media (87.2%), followed by tablet PCs (53.2%) and desktop computers/laptops (43.4%).

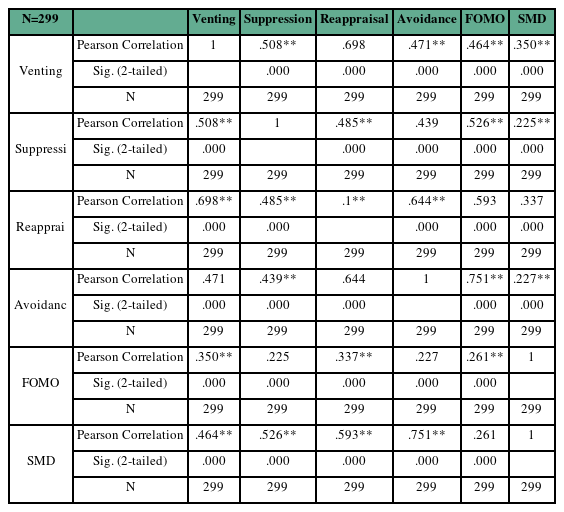

Pearson Product-moment correlations (with the pair-wise exclusion of missing cases) are conducted in order to reveal correlations between the dependent and independent variables. The analysis reveals that the dependent variable and independent variables are positively correlated (Table 2).

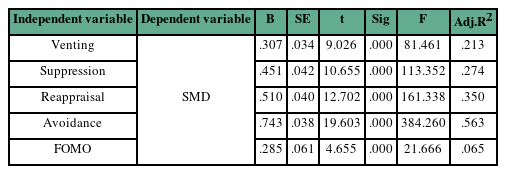

To assess the relative predictive values, multiple linear regression analysis is conducted between the dependent and independent variables.

The findings of the study reveal that venting, suppression, reappraisal, avoidance, and FOMO determine social media dependency (SMD). The ß coefficients indicate the highest relationship between avoidance and SMD (ß= ,743, t=19.603, p=,000), followed by reappraisal and SMD (ß= ,510, t=12.702, p=,000), suppression and SMD (ß= ,451, t=10.655, p=,000), and venting and SMD (ß= ,307, t=9.026, p=,000). The ß coefficient is lowest for the relationship between FOMO and SMD (ß= ,285, t=4.655, p=,000), though is significant (see Table 3). Thus, H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 are supported.

Discussion

The current study reveals that social media dependency is determined by the dimensions of communication anxiety regulation; venting, suppression, reappraisal, and avoidance. The most intense relationship is indicated between avoidance - the act of staying away from something or a situation undesirable - and SMD. This finding suggests that, as a form of escape, transgender individuals direct their energy to social media use in order to stay away from the pressures of the offline world.

The second strongest relationship is found between reappraisal and SMD. In terms of reappraisal, social media offers various avenues for transgender individuals, including online social networks, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. For instance, when a transgender individual encounters a negative situation in the offline world, they can easily turn to social media to seek peer support and psychologically reframe that negative experience in a positive way. Thus, reappraisal on social media appears to be a defense strategy among transgender individuals.

The third highest relationship is revealed to be between suppression and SMD. Intense social media use can assist transgender individuals who remain in the closet and are indecisive about coming out to their social circles. In this context, suppression can be considered by taking various dimensions of being transgender, ranging from gender dysphoria to building romantic relationships. When one does not have the opportunity or will to express their actual self, social media platforms may emerge as saviors, for allowing its users the options of remaining anonymous, physically distant, and selective in terms of building social bonds.

Venting and SMD have the fourth-highest relationship. The reason venting comes after avoidance, reappraisal, and suppression might be the fact that transgender individuals may not feel that they are free enough to express their emotions on social media. In Turkey, the use of social media is highly restrictive not only for transgender individuals but also for the overall population. The most recent restrictive action, taken by Turkey’s government has been preparing a new draft of legislation called The Disinformation Law. The legal proposal consists of ambiguous 40 clauses that cover a variety of topics ranging from regulation of the Internet to press law (Özturan, 2022). When one considers the fact that 160.169 investigations had been recorded by September 2021 which were related to insult claims against the President of Turkey via social media (Topuz, 2021), it is understandable that transgender individuals might feel that they can potentially encounter negative reactions on social media if they express their actual selves.

The lowest, but still significant, relationship is recorded between FOMO and SMD. This is a critical finding when one considers the fact that FOMO is one of the primary factors that triggers SMD among individuals (Alutaybi et al., 2020). But in the case of transgender individuals, FOMO remains a mild factor, when compared with the dimensions of communication anxiety regulation.

Even though the current study offers resourceful insights, it also has several limitations. Firstly, the use of a self-report questionnaire is both an advantage and a disadvantage. While self-reporting enables individuals to express their own perspectives, behavior-based studies can provide a further understanding of the issue under question. Future research is needed to explore whether intense social media use, as a result of communication anxiety and fear of missing out, encourages positive activities such as reaching out for community support, self-help, and information seeking. This topic is worth for exploration in the context of transgender individuals, as online engagement with productive communities and content has the potential to contribute to their physical and psychological well beings. The second limitation derives from applying the snowball sampling technique for the data collection. While snowball sampling provides the opportunity to reach specific groups of individuals, the generalizability and representativeness of the findings in the intercultural context can be questioned. Future researchers can test the intercultural validity of the current study, by applying the same research perspective towards various social and cultural contexts.

Notes

Transgender individuals will be referred as “they/them” throughout the text, as “they/them” pronoun stands as a gender-neutral approach to refer individuals who may not belong to a particular gender identity.