Communicating Zika at the wake of the epidemic : a content analysis of the U.S. newspaper coverage of Zika virus

Article information

Abstract

Drawing on framing theory, this study examined U.S. newspaper coverage of Zika virus (ZIKV) at the wake of the epidemic in early 2016. Through a quantitative content analysis, this study examined the major themes, the tone, attributions of causes and solutions, potential health consequences, and source cited. The analysis revealed that the newspaper coverage of ZIKV predominantly incorporated a neutral tone rather than a negative one as suggested by the findings of previous research. The coverage imbued two competing themes - action-control and panic-fear, which indicated journalists’ parallel attention to both the risk-provoking and the risk-control aspects of the crisis. In addition, exaggerations about the health risks of ZIKV posed to humans were also identified. Theoretical and practical implications were discussed.

Introduction

On February 1, 2016, the unprecedented outbreaks of Zika virus (ZIKV) in South America prompted the WHO to classify Zika infection as a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” (PHEIC) (CDC, 2016), which fueled widespread attention and concerns about the health crisis. Amid scientific uncertainty, the role of news media becomes vital in providing timely information and explaining the underlying issues to the public (Brodie, Hamel, Altman, Blendon, & Benson, 2003). Moreover, news media may impose a more pronounced influence on the public’s attitudes and behaviors in the emerging stage of Zika epidemic.

However, when facing emergent public health threats, such as Ebola, U.S. policymakers and news media have been criticized for creating communication chaos that should be avoided in future health-related communications (Ratzan & Moritsugu, 2014). Drawing upon framing theory, the present study aims to find out how newspapers in the United States address the crisis amidst scientific uncertainty related to the nature of ZIKV infection. Through a content analysis of four major newspapers in the United States, this study examined the major themes, the primary tone of news stories, attributions of causes and solutions, source cited and the health consequences of ZIKV infection.

The study is particularly interested in the news articles published before the causal relationship was confirmed between ZIKV and severe birth defects (e.g. microcephaly) in April 2016 by the CDC. Theoretically, it provides a comprehensive framework to examine news coverage of health crisis based on existing theories. Practically, it provides baseline data for health journalists and policy makers to improve the effectiveness of managing health crisis from a mass communication perspective.

Literature Review

Framing Theory

The concept of framing provides a venue for understanding how realities are socially constructed via the influence of the mass media (Borah, 2011). Framing theory posits that the media promote particular parameters to interpret an issue, structuring public perceptions of the issue (Entman, 1993). On the one hand, frames in the media induce social reality and meaning through selection and exclusion of symbolic representations (Entman, 1993). On the other hand, the framing process in the media reflects dominant values and culture in a society by highlighting certain aspects of an issue while downplaying others (Goffman, 1974; Ryan, Carragee, & Meinhofer, 2001; Van Gorp, 2007).

Framing theory has been employed in various contexts, such as in the public discussions of sporting events on social media (e.g., Burch, Frederick, & Pegorar, 2015; Yang, Wang, & Billings, 2016), news coverage of science and technology (e.g., Strekalova, 2016), and the television news portrayals of political issues (e.g., Liang, Tsai, Mattis, Konieczna, & Dunwoody, 2014). In health communication, framing has important theoretical and practical implications for two major reasons. First, substantial attention is associated with health-related news in the public (Brodie et al., 2003). For instance, health and medical news are ranked third among all news topics sought by online news audiences (Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2010). Second, the media serve as a key liaison between researchers, policy makers, and the general public, especially in the initial stage of health crisis (Ratzan & Moritsugu, 2014). While the public rely on the media to get health-related information, mediated portrayals of health issues, especially emergent epidemic hazards, could cause misunderstanding and panic among the audience (Ratzan & Moritsugu, 2014).

Understating the frames in the media is the first step in creating efficacious communication among policy-makers, the media, and the public. Content analysis holds the promise to provide such knowledge. As Kolbe and Burnett (1991) wrote, “Content analysis provides an empirical starting point for generating new research evidence about the nature and effect of specific communications” (p. 244). Presented here is a quantitative content analysis examining U.S. newspaper coverage of ZIKV in early 2016 when the epidemic just flared. Drawing on a sociological approach to framing, the study examined the major themes, predominant tones, the framing of cause and treatment responsibility, and the source cited in newspaper coverage of ZIKV.

Framing and News Coverage of ZIKV

On February 1, 2016, the unprecedented outbreaks of Zika virus in South America prompted the WHO to classify Zika infection as a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” (PHEIC) (CDC, 2016), which fueled widespread attentions and concerns about the health crisis. Amid scientific uncertainty, the role of news media becomes vital in providing timely information and explaining the underlying issues to the public (Brodie et al., 2003). Moreover, news media may impose a more pronounced influence on the public’s attitudes and behaviors in the emerging stage of Zika epidemic.

By promoting particular parameters to interpret an issue, news media impact audiences’ perceptions about an issue (Entman, 2004). Specifically, framing highlights and prioritizes certain aspects of a topic (Entman, 2004). For instance, examining the newspaper portrayal of obesity in Sweden, Sandberg (2007) found that obesity was commonly constructed as more of an appearance dilemma than a health problem. Differently, in U.S. Black newspapers, obesity was presented as an epidemic in ethnic minorities with an emphasis on individual responsibility (Lee & Len-Rios, 2014). In addition to perception, framing also impacts the audiences’ attitudes and behaviors (Entman, 2004). For example, emphasizing health disparity between Blacks and Whites, newspaper coverage of colon cancer led to lower intention in participating cancer screening among Black participants (Nicholson et al., 2008).

Consistent use of frames in the media holds the potential to shape public perceptions and attitudes (Entman, 1993). In the initial stage of the Zika epidemic, researchers had limited knowledge regarding the mechanism of ZIKV transmission and the health outcomes. The study is particularly interested in the news articles published before the causal relationship was confirmed between ZIKV and severe birth defects (e.g., microcephaly) in April 2016 by the CDC. Amid scientific uncertainty, the news media may impose particularly significant influences on public perceptions and beliefs about ZIKV. As such, an examination of the thematic frames employed in news reporting of ZIKV is warranted:

RQ1: What are the dominant themes used in the U.S. newspaper coverage of ZIKV?

Unlike other health issues, the reporting of pandemic situations tends to be pressing and challenging due to uncertainty and information scarcity. In addition to a factual event, an epidemic is also a special narrative that has deep cultural roots in Western history (Alcabes, 2009). The fear pervaded¬ by the iconic images of deadly pandemics (e.g., the medieval plague or the Black Death) could be reactivated with the reporting of a new epidemic (Alcabes, 2009). Such socio-cultural roots can be part of the frames used by the media to construct meaning and realities of pandemics. Consequently, the frames of fear and alarmism are prevalent in news coverage of emerging health risks (Southwell & Thorson, 2015).

In the process of meaning construction, fearful words and metaphors imbued in the frames of alarmism also construct the tone of frames (Lakoff, 2004). For instance, with emotionally charged languages, news coverage of SARS perpetuated alarmism by attenuating the worst-case scenarios (Berry, Wharf-Higgins, & Naylor, 2007). Similarly, predominant negative tone was found in newspaper coverage of the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak (You et al., 2017) and foot and mouth disease outbreaks (Cannon & Irani, 2011). Portraying an issue in a negative tone could increase public awareness (Sheafer, 2007). However, overly alarming coverage may also foster unnecessary fear. For example, negative news about clinical trials were associated with decreased willingness to participate in clinical trials (Len-Rios & Qiu, 2007).

Drawing on the findings of previous work, a hypothesis was proposed to investigate the predominant tone used in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV:

H1: Negative tone would be the most prevalent in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV.

Besides prevalent themes, framing analysis also pays particular attention to the attributes included in a message (Scheufele, 1999). The attributes include information related to the substantial aspects of an issue (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997). Among these attributes, cause and solution attributes are two important ones as they identify the causal agents, locate responsibility, and thus distribute benefits and burdens (Iyengar, 1989; Stone, 1989).

From a perspective of framing theory, the attribution of causal and treatment responsibility is a form of social knowledge (Iyengar, 1989). Framing of causal responsibility relay the origin of a problem, while framing of treatment responsibility delineates “who or what has the power either to alleviate or to forestall alleviation of the problem” (p. 879). For instance, the representation of a social issue (e.g., poverty) highlighted socio-cultural context and collective responsibility, government and the society were perceived as accountable (Iyengar, 1989). In contrast, individuals were blamed for their own choices and situations when the portrayal of an issue focused on personal stories (Iyengar, 1989).

The attribution of causality and treatment transfers meanings about responsibility, which could ultimately shape an individual’s attitudes and behaviors (Sun et al., 2016). The news coverage of health issues has been criticized for diverting public attention away from societal causes of diseases, such as poverty, social inequalities, policy-level issues, and unethical business practices (Salmon, 1989; Wallack, Dorfman, Jenigan, & Themba, 1993). For instance, news coverage of schizophrenia stressed the individual’s responsibility of causing and fixing the issue (Yang & Scott, 2017). Similarly, in the context of obesity, the individualization of the causes and solutions was constantly perpetuated in the media, while social responsibilities were largely ignored (Kim & Willis, 2007).

Drawing on the findings from previous work, two hypotheses were proposed to examine the attributions of causes and solutions in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV:

H2: The causes of ZIKV would be more likely to be framed at the individual-level than at the societal-level in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV.

H3: The treatment responsibility of ZIKV would be more likely to be framed at the individual-level than at the societal-level in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV.

Based on the lessons learnt from previous epidemics (e.g., SARS), Ratzan and Moritsugu (2014) advocated to employ evidence-based health communication diplomacy. In the presence of an emerging epidemic, journalists and public health professionals tend to provide information related to the symptoms and health consequences to fulfill the public’s educational needs (e.g., Anhang, Stryker, Wright, & Goldie, 2004; Young, Tully, & Dalrymple, 2018). In addition, journalists commonly rely on official sources to generate content due to the lack of specialized medical knowledge (Schudson, 2006). Moreover, because of their expertise and their access to more accurate information (Fico, 1984), expert sources, such as doctors, government, and other elite sources, often influence health news reporting, even unintentionally (Viswanath & Emmons, 2006).

As such, a research question centering on the health consequences and a hypothesis regarding the sources cited in the news coverage were proposed:

RQ2: What are the health consequences of ZIKV infection covered by major U.S. newspapers?

H4: Expert sources would be cited more frequently than non-expert sources in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV.

Method

Sampling

Major daily newspapers influence news coverage by other sources (Chapman, 2004), providing a good indicator of general news content across media (Holder & Treno, 1997). Four national newspapers with high circulations in the United States were used to collect data, including The Washington Post, New York Times, USA Today, and Wall Street Journal (Alliance of Audited Media, 2013). The search key words included Zika and ZIKV. LexisNexis and the archival database of Wall Street Journal were employed to retrieve news articles within the time frame between January 2015 to March 2016.

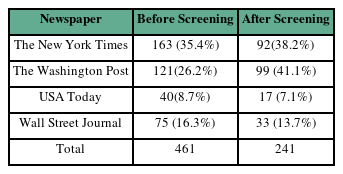

A search of the newspapers’ archival databases using the two keywords within the time frame initially yielded 461 articles. However, many articles merely mentioned ZIKV in a marginal manner. As this study aimed at exploring newspapers’ coverage of ZIKV, articles not focusing on ZIKV were excluded for analysis. For instance, articles focused on Brazil’s political crisis and mentioned Zika virus in a marginal manner were excluded from the final sample. Two coders screened a randomly selected 30% of the 461 news articles (n = 139) and reached an intercoder reliability of κ (Cohen’s Kappa) = .89 for screening. The primary investigator screened the rest of the articles. In the end, a total of 241 news articles were included in the final sample. Table 1. presents screening results by newspaper.

As the Table 1. confirms, the final sample (n = 241) consists of 99 (41.1%) articles from The Washington Post, 92 (38.2%) from The New York Times, 33 (13.7%) from Wall Street Journal, and 17 (7.1%) from USA Today. The earliest article discussing ZIKV was published in September 2015 by Wall Street Journal. After that, it was until December 2015 (n = 6, 2.5%) and January 2016 (n = 56, 23.2%) that the four national newspapers started to cover the epidemic. In addition, newspaper coverage of ZIKV reached its peak (n = 119, 49.4%) in February, which coincided with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring Zika virus a PHEIC on February 1, 2016.

Measurement

Each article in the final sample was coded based on the following dimensions: demographic information, major theme of the article, tone of the article, cause of the infection, cause, solution, source cited, and the associated health consequences.

Codebook

Inductive coding techniques were utilized to establish the coding categories to ensure the diversity and validity of the coding schemes. The study employed thematic analysis methods using constant comparative methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The coding categories were established through three phases of coding. In the first round of coding, the primary investigator read all the news articles in the final sample to get a general idea about the newspaper coverage of ZIKV. In the second round of reading, a randomly selected 30% (n = 72) of all the articles in the final sample were read by the primary investigator. Mutually-exclusive categories were created by summarizing and comparing the themes and approaches embedded in the news articles (Sanderson, 2013). In this process, the researcher reduced and summarized the categories as much as possible, ensuring the correctness and the exhaustiveness of the categories (Sanderson, 2013). As such, initial categories were established. In the third phase, the usefulness and reliability of the initial categories were examined (Suter, Bergen, Daas, & Durham, 2006). Another randomly selected 50 (20.7%) news articles were coded to test the developed categories. New observations were accounted for and included if significant reliability of such category occurred (Sanderson, 2013).

As such, the coding categories were established for major themes, causes, treatment responsibility, and the associated health consequences. Examples for major coding categories are included in Table 2. All categories were coded based on presence and absence, where present = 1 and absent = 0.

Major themes emerged in the coverage of ZIKV were identified to find answers for RQ1. A theme was used as the unit of analysis for this research question. Five major themes were identified in the coverage of ZIKV: panic-fear, diagnosis of ZIKV, action-control, scientific uncertainty, and other themes. The panic-fear theme was coded when news articles emphasized the alarmism, portrayed ZIKV as an epidemic, and focused on the peril of the disease. In Action-control was coded when articles downplayed the alarmism and focused on active actions to fight against the disease, such as the report of scientific breakthrough, governmental actions, guidelines and advisories, and researchers’ efforts in deciphering and combating the disease. Diagnosis of ZIKV and other associated health outcomes was coded when news articles focused on newly identified cases. The theme of uncertainty was induced when news articles addressed scientific uncertainty that reflected the state of knowledge about ZIKV.

H1 remained that negative tone would be the most prevalent tone in newspaper coverage of ZIKV. An individual article was used as the unit of analysis for H1. Each news article was coded as positive, neutral, or negative. A positive article referred to “desirable outcomes/news” (Lee & Len-Rios, 2014), such as scientific breakthrough, efforts in fighting against ZIKV, or decrease in prevalence. An article was coded as negative when “undesirable outcomes/news” served as the predominant topic (Lee & Len-Rios, 2014), such as links between ZIKV and negative health outcomes, ineffective control of the virus, increase in prevalence rate, prolonged vaccine development, or lack of resources for combating the disease. An article was coded as neutral when it was factual in nature (e.g. informing the public about the updated guides from CDC) or contained both negative and positive orientations (Lee & Len-Rios, 2014).

H2 posited that individual-level causes would be covered to greater extent than societal-level causes. Four categories of causes were identified: mosquito, sexual transmission, pass from mother to fetus, and blood transfusion issues. Sexual transmission, mother-to-child transmission, and mosquito bites were coded as individual-level causes since they stressed on micro-level factors, such as individual qualifications and behaviors (see Kim & Willis, 2007; Zhang et al., 2015). Blood transfusion issues was coded as a societal-level cause since it emphasized on social, cultural, environmental and policy-level factors (Kim & Willis, 2007; Zhang et al., 2015).

H3 surmised that individual-level solutions would be discussed to greater extent than societal-level solutions in newspaper coverage of ZIKV. A total of eight proposed solutions were identified, including destroying mosquito habitats, avoiding traveling to affected areas, self-deferral, governmental and societal actions, avoiding mosquito bites, developing vaccine, using genetically modified mosquitoes to control the vector, and regulation on blood supply. Similar to the coding of solutions, four were coded as individual-level solutions. They are destroying mosquito habitats, avoiding traveling to affected areas, self-deferral, and avoiding mosquito bites. Four societal-level solutions were also identified, including governmental and societal actions, developing vaccine, using genetically modified mosquitoes to control the vector, and regulation on blood supply.

RQ2 investigated the associated health consequences of ZIKV. While no conclusive causal relationship has been established between ZIKV and severe health outcomes (e.g. microcephaly, Guillain-Barre syndrome, death, etc.), the associated health consequences were coded when newspaper articles explicitly provided the associated health outcomes or addressed the potential link. Eight categories of health outcomes were identified, including microcephaly, mild flu-like symptoms (e.g. rashes, fevers, etc.), asymptomatic, death, Guillain-Barre syndrome and temporary paralysis, mental illness and autism, and others.

H4 posited that expert sources would be more frequently cited than non-expert sources in newspaper coverage of ZIKV. Expert sources consisted of seven categories, including academic researchers, the CDC, the WHO, governmental officials (not including CDC and WHO), doctors, FDA, non-profit organizations, and other expert sources. Non-expert sources included pregnant women diagnosed with ZIKV infection, families of the patient and lay persons.

Intercoder Reliability

The author and an additional English-speaking coder were trained and coded a randomly selected 20% (n = 50) of all articles in the final sample. A total of three rounds of coding were conducted, in which discrepancies in their coding were discussed and resolved by revisiting the operational definitions and relevant literature. Using Cohen’s Kappa, they reached an overall intercoder reliability of .82 (.81 for tone, .82 for dominant themes,.86 for cause, .77 for solution, .85 for cause attributions, .89 for solution attribution, .88 for sources, and .83 for health outcomes). Kappa scores above .75 illustrate acceptable agreement (Olswang, Svensson, Coggins, Beilinson, & Donaldson, 2006).

Results

RQ1 queried about the most prominent themes surrounding ZIKV in U.S. newspapers. Five major themes were identified in the coverage of ZIKV: panic-fear, diagnosis of ZIKV, action-control, scientific uncertainty, and other themes. The most prominent themes were action-control (n = 183, 75.9%), followed by panic-fear (n = 151, 62.7%), scientific uncertainty (n = 105, 43.6%), diagnosis of Zika infection (n = 40, 16.6%), and other themes (n = 29, 12.0%). All themes reached their peaks in newspaper coverage in February 2016 after the WHO classified ZIKV as an international public health emergency.

H1 maintained that negative tone would be the most prevalent tone. Overall, the most prevalent tone was neutral tone, which was identified in 52.3% (n = 126) of all the news articles analyzed, followed by negative tone (n = 85, 35.3%) and positive tone (n = 30, 12.4%). Further statistical analysis revealed significant differences in the use of affective attributes over the months, χ2 (2, N = 241) = 56.88, p < .001. Neutral tone was used to greater extent than positive and negative tone. Consequently, H1 was not supported.

H2 posited that newspaper coverage would be more likely to attribute Zika virus infection to individual-level causes than societal-level causes. Among the articles analyzed, 67.2% (n = 162) of them addressed causes of ZIKV. A total of 251 mentions of causes were found. The most prominent cause was mother-to-child infection (n = 107, 42.6%), followed by mosquito bites (n = 103, 41.0%), sexual transmission (n = 36, 14.3%), blood transfusion (n = 5, 2.0%). As such, 98.0% of the causes were attributed at the individual level while only 2.0% were at the societal-level. The result of chi-square analysis revealed a significant difference in the use of individual-level attributions and societal-level attributions, χ2 (1) = 92.2, p < .001. Individual-level causes were mentioned to greater extent than societal-level causes. Consequently, H2 was supported.

H3 remained that individual-level solutions would be mentioned more frequently than societal-level solution to combat ZIKV in newspaper coverage of ZIKV. Overall, 52.7% (n = 127) of all the articles in the final sample proposed at least one solution. Among all the mentions of solutions (n = 144), 64.6% (n = 93) were individual-level solutions, while 35.4% (n = 51) were societal-level solutions. The most prevalent solution was destroying mosquito habitats (n = 30, 20.8%), followed by avoiding traveling to infected areas (n = 29, 20.1%), governmental and societal actions (n = 19, 13.2%), avoiding mosquito bites (n = 18, 12.5%), self-deferral (n = 16, 11.1%), developing vaccine (n = 13, 9.0%), using genetically modified mosquitoes to control the vector (n = 11, 7.6%), regulations of blood supply (n = 8, 5.6%). The result of chi-square analysis revealed a significant difference in the use of individual-level attributions and societal-level attributions, χ2 (1) = 12.3, p < .001. Individual-level causes were mentioned to greater extent than societal-level causes. Consequently, H3 was supported.

RQ2 queried about the health consequences discussed in the news stories. Approximately 71.0% (n = 171) of all the articles in the final sample discussed health consequences. A total of 303 mentions of health consequences were identified. Microcephaly (n = 156, 51.5%) was the most widely discussed health outcomes, followed by Guillain-Barre syndrome and temporary paralysis (n = 63, 20.8%), mild symptoms (e.g., rashes, fevers, etc.) (n = 46, 15.2%), asymptomatic (n = 21, 6.9%), other health consequences (n = 9, 3.0%), death (n = 5, 1.7%), and mental illness and autism (n = 3, 1.5%).

H4 posited that expert sources would be cited more frequently than non-expert sources. Overall, 85.5% of all the news articles (n = 206) cited expert sources and 9.1% (n = 22) cited non-expert sources. A total of 401 mentions of sources were identified. Among them, 94.5% were expert sources, which included academic researchers (n = 137, 34.2%), the CDC (n = 92, 22.9%), the WHO (n = 44, 11.0%), other health department officials (n = 58, 14.5%), and other expert sources (n = 15, 3.7%), doctors (n = 13, 3.2%), FDA (n = 12, 3.0%), and non-profit organizations (n = 8, 2.0%). In addition, non-expert sources consisted 9.1% (n = 22) of all the mentions of sources. The result of chi-square test revealed that a significant difference in the use of expert sources and non-expert sources, χ2 (1) = 147.20, p < .001. Expert sources were more frequently employed than non-expert sources in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV. Consequently, H4 was supported.

Discussion

Overall, the newspaper coverage of ZIKV employed panic-fear and action-control as two competing themes. The findings were partially consistent with expectations of how the press covers risk-provoking public health outbreaks derived from the previous science communication literature. For instance, their reporting of health consequences reflected both timely updates and information that exaggerated the health risks posed to humans (e.g., autism, mental illness). In addition, consistent with the patterns identified in the existing literature, causes and treatment responsibility of ZIKV were framed predominantly at the individual-level. However, unlike the reporting of other emerging epidemics, the newspaper coverage of ZIKV predominantly employed neutral tone, instead of an overly negative one. Drawing upon expert sources, the four newspapers balanced a sense of alarm with a parallel attention to the attempts by public health agencies to control the virus’ impact on population health.

The newspaper coverage about ZIKV was imbued with two competing themes—fear-panic and action-control. In addition, contrary to the findings from previous work on tone, newspaper coverage of ZIKV was not overly negative. Instead, the coverage was largely neutral. However, from a perspective of social amplification of risk, reassuring messages may not counter the effects of fear-risk based messages, especially in the presence of large amount of information (Kasperson et al., 1988). For example, the public’s perceptions about genetically modified foods were more likely to be swayed by the representation of risks than that of prevention (Frewer, Miles, & Marsh, 2002).

While the methods of the study did not allow for measuring exposure to or influence from news articles about ZIKV, data from concurrent public polling may provide useful context for the potential causal inference between news media coverage and public perception. In a poll conducted in March 2016 with approximately 1,000 respondents, 42% of the respondents believed that people infected with ZIKV would be likely to die; 44% believed that ZIKV would cause noticeable symptoms (APPC, 2016b). However, the majority of people infected with ZIKV would be asymptomatic or only have flu-like symptoms which commonly disappear within a week (WHO, 2015).

In terms of the reporting of the potential health outcomes, both evidence-based information and exaggerations were included in the newspaper coverage of ZIKV. For instance, potential health outcomes included death and mental illness in adults and autism in children. This is consistent with the findings from previous work that news media tended to sensationalize public health crisis (e.g., Fung, Namkoong, & Brossard, 2011; Ihekweazu, 2017). One explanation could be that framing is the outcome of negotiation processes between the media and their sources (Lee & Basnyat, 2013; Vliegenthart & Van Zoonen, 2011). For instance, in the context of a new epidemic, while experts provide different opinions, the media tend to have a ubiquitous bias in favor of the worst-case scenarios (House of Commons, 2011). The pursuit of a higher news value may play a role in the phenomenon (Signorielli, 1993). As Signorielli (1993) posited, it is problematic that health news exaggerates and entertains since it is ultimately driven by what sells.

Consistent with the findings from previous work (e.g., Shih et al., 2011), expert sources were predominantly used in the coverage of ZIKV. Health authorities and scientists are credible and trustworthy information sources, as they have access to the most up-to-date findings and thus may impact health policies (Clarke, 2008; Conrad, 1999). While alarming messages and uncertainties abounded, such alarming messages were built on credible sources, which could effectively trigger preventative actions in the public. For instance, Southwell et al., (2016) found that increases in online searches and information sharing about ZIKV could be attributable to announcements from experts. Their findings suggested that coverage of expert sources may create important education opportunities to communicate preventative methods. Lending support for their findings, citing expert sources helped to correct misconceptions about ZIKV on social media (Vraga & Bode, 2017).

With limited knowledge regarding the mechanism of ZIKV infection in early 2016, it could be challenging for the news media to secure a balanced representation between factual information and scientific uncertainty. Scientific uncertainty was found to be the third most dominant theme. On one hand, discussions of scientific uncertainty could leverage the public’s trust about the news sources (Covello, Peters, Wojtecki, & Hyde, 2001). For instance, without discussions of scientific uncertainty, news audiences might perceive changes in information as the results of mistakes, rather than that of scientific progression (Mebane, Temin, & Parvanta, 2003). On the other hand, it may serve as a quantitative measurement of risk, which could exacerbate the panic and fear associated with ZIKV. Future research could be conducted to explore how discussions of scientific uncertainty impact audience’s attitudes and behaviors in the context of an emerging epidemic.

Amidst scientific uncertainty, more than half of the articles covered causes and solutions to ZIKV. In addition, the attribution of causes and treatment responsibility was predominantly made at the individual-level. Such attribution may help to mobilize immediate actions in the public. However, the individualization and decontextualization of health issues overlooked the social-environmental factors that may impact an individual’s health-related choices and behaviors. For instance, the WHO recommended national water and sanitation intervention programs that target at eliminating potential mosquito breeding sites (WHO, 2017). Recognizing collective responsibilities of health could help to induce political and social efforts to building an environment that facilitate healthy options and behaviors (Dorfman, Wallack & Woodruff, 2005).

It is important to note that the study has several limitations. The findings of this study may not be extrapolated to all news media platforms, since the study merely analyzed newspaper coverage of ZIKV. To achieve greater generalizability of the findings, future research could include news from other media platforms, such as TV, radio, and social media. In addition, the study focused on newspaper coverage in the initial stage of the ZIKV epidemic. As news trends could be impacted by competing themes in the news cycle (Shih, Wijaya, & Brossard, 2008), continued research about the mediated portrayal of ZIKV is warranted. As Zika virus imposes ongoing risks to the public health, continued investigations on the news coverage of ZIKV are warranted. Finally, one major limitation of the study lies in the lack of concurrent public opinion data. Limitations aside, the findings of this study could inform future experimental designs that examine the relationship between news media portrayal and public perceptions of ZIKV. For instance, the analysis revealed two competing themes – action-control and panic-fear. Little is known about the effects of such mixed frames (Chong & Druckman, 2007), which alludes a need for examining the impact of news coverage on audiences’ attitudes and behaviors.

Practically, the findings of the study underscore several courses of actions for health journalists. First, answering the calls of Ratzan and Moritsugu (2014) for evidence-based health communication, truthful representations of an issue are needed to cultivate a well-informed public. When news coverage of a crisis is driven by the pursuit of greater news value, exaggerations and misinformation could occur. In the presence of serious public health threat, it is vital for the news media to fulfill its social responsibility by providing truthful representations of an issue (Lambeth, 1992). Second, a more balanced coverage is needed for the attributions of cause and solution. By including more information about societal-level solutions, health journalists could contribute to reframing the notion of health and fostering an environment that facilitates healthier options.

Theoretically, this study provided a comprehensive framework to examine news coverage of ZIKV based on framing theory. The incorporation of both inductive and deductive coding methods served as a major contribution of the study. Such coding techniques could help to capture both generic and unique attributes in the framing of ZIKV. In addition, the coding categories generated by this study could serve as a useful coding framework for future assessment of coverage of ZIKV and other risk-provoking public health emergency.

Conclusion

This study shed light on the newspaper coverage of ZIKV in the initial stage of the epidemic. Analysis indicated important consistency and differences between the news coverage of ZIKV and that of previous outbreaks. The overall newspaper coverage of ZIKV was not as alarming and negative as what existing literature suggested. However, exaggerations and misinformation were found in the reporting of health consequences of ZIKV. In the presence of an emerging epidemic, it is potent for the media to provide truthful representations of facts and relevant contexts that give the facts meaning (Lambeth, 1992). The study also contributes methodologically by both generic and unique coding categories, providing new directions for content analysis studies on emerging health crisis.