The platform is the message? Exploring the relation between different social networking sites and different forms of alcohol use

Article information

Abstract

Scholars have drawn attention to the role of social networking sites (SNS) in individuals’ alcohol use. This cross-sectional study (N=905; Mage=20.78; 78% females) aimed to explore the relation between exposure to alcohol across Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp and different alcohol-related outcomes (binge drinking and alcohol use). Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypotheses. First, the results indicate that Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp are positively related to alcohol use through attitudes and social norms towards alcohol use. Second, Snapchat and WhatsApp also appear to be associated with binge drinking. This might be explained by the fact that users consider the former platforms to be more suitable to share problematic forms of drinking. This study indicates that different platforms relate to different alcohol outcomes and can therefore not be treated as homogenous constructs when examining the relationship between SNS and alcohol consumption.

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is globally considered as major health problem, causing nearly 3.3 million deaths annually (WHO, 2014). Especially, emerging adults (EA), defined as individuals between the ages of 18 and 25, are considered to be an at risk group. According to Arnett’s theory of emerging adulthood (2000), emerging adulthood is a distinct period of life between adolescence and adulthood. EA have not acquired adult roles such as parenthood and marriage yet, but unlike adolescents, they have the opportunity to fully explore different domains in life (Arnett, 2000). Parental control decreases in this stage of life, peer contacts are very important and individuals experiment with substances as part of their identity exploration and formation (Arnett, 2005; Neighbors et al., 2007; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). It has been noted that alcohol use and misuse peaks in this stage of life. Approximately, 52% of the Belgian emerging adults regularly consume alcohol (De Bruyn et al., 2018). Additionally, 60% has engaged in binge drinking which is perceived to be a more extreme form of alcohol use whereby individuals consume at least four (women) or five (men) glasses of alcohol within two hours (Van Damme et al., 2018). Considering the short-term (e.g., car accidents) and long-term risks (e.g., liver cirrhosis) associated with alcohol use, it is important to understand the factors contributing to emerging adults’ alcohol consumption.

Several determinants have already been shown to influence individuals’ drinking behaviors including, individual (e.g., personality), peer (e.g., peers’ alcohol use) and parental factors (e.g., parental monitoring) (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014; Rosiers et al., 2018). Although often neglected in studies examining the determinants of alcohol use, scholars have pointed towards the role of social networking sites (SNS) in alcohol use (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Curtis et al., 2018). It has been argued that individuals exposed to alcohol on SNS increase their alcohol consumption, engage in heavy drinking, and show positive attitudes towards alcohol use (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Geusens & Beullens, 2018). Although these studies generated important insights, several questions remain unanswered.

First, most studies have focused on the effects of Facebook (D’Angelo, Zhang, Eickhoff, & Moreno, 2014) or treated social media as one homogenous construct (Geusens & Beullens, 2018). Although Facebook remains a popular platform among emerging adults, it has been shown that other platforms including Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp become increasingly popular in this subgroup (Smith & Anderson, 2018; Vanhaelewyn & De Marez, 2018). Moreover, alcohol appears to be omnipresent on these platforms as well (Boyle, Earle, LaBrie, & Ballou, 2017; Hendriks, van den Putte, Gebhardt, & Moreno, 2018). Resultantly, we intend to comparatively examine whether exposure to alcohol-related references is associated with emerging adults’ alcohol use across different platforms.

Second, this study aims to determine whether the uses of different SNS are associated with different alcohol-related outcomes. So far, studies have interchangeably examined the impact of SNS on general alcohol use and problematic drinking patterns such as binge drinking (i.e., consuming at least four glasses for women and five for men within two hours) (Curtis et al., 2018; Geusens & Beullens, 2018). Yet, scholars highlighted the importance of distinguishing between alcohol use and binge drinking (Laghi et al., 2016; Morean et al., 2014). Whereas consuming alcohol is by many perceived to be socially acceptable, binge drinking is usually not as it is a riskier form of alcohol consumption (Gmel et al., 2011; Kalinowski, & Humphreys, 2016; WHO, 2011, 2014). Even when individuals consume equal amounts of alcohol, individuals engaging in binge drinking experience more permanent negative health-related outcomes (e.g., brain damage) due to the high alcohol intake within a short timeframe (José et al., 2000; Rehm et al., 2003; WHO, 2011, 2014).

This distinction between different alcohol outcomes is especially important in the social media context. Particularly, there are indications to assume that the nature of alcohol-related references varies between platforms (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Boyle et al., 2017; Utz, Muscanell, & Khalid, 2015). Considering that some platforms appear to be more appropriate to share more problematic drinking patterns (e.g., binge drinking) (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016), the current study aims to examine whether exposure to these platforms is associated with binge drinking, as opposed to platforms where mainly more socially accepted forms of drinking are shared (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Hendriks, van den Putte & Gebhardt, 2018).

Literature Review

Alcohol references on SNS

Content analyses indicate that alcohol portrayals are ubiquitous on SNS (Beullens & Schepers, 2013; Hendriks et al., 2018). These references are often shown in a positive context in which alcohol use is an intrinsic part of going out and having fun with friends (Beullens & Schepers, 2013). Additionally, users regularly receive positive feedback on these references (e.g., likes & comments) (Beullens & Schepers, 2013). Drawing on theoretical models such as the social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), studies evidence that, although alcohol-related content on social media (partly) reflects prior offline alcohol use, exposure to these positive references also impacts subsequent real-life alcohol use (Erevik et al., 2017; Geusens & Beullens, 2017).

Explaining the relation between SNS and alcohol use

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) has frequently been used as a background to understand how exposure to alcohol references is related to offline alcohol use (Geusens & Beullens, 2017; Litt & Stock, 2011). This theory (Ajzen, 1991) posits that attitudes and social norms shape individuals’ behavioral intentions and subsequent behaviors. First, attitudes refer to the extent to which an individual attaches positive or negative valence to certain behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). Individuals showing more positive attitudes towards alcohol use consume alcohol more frequently (Houben et al., 2010).

Second, social norms appear to be an important determinant of alcohol use (Ajzen, 1991). Thereby a distinction between descriptive and injunctive norms should be made (Chung & Rimal, 2016). Descriptive norms refer to beliefs about the extent to which peers engage in behaviors, whereas injunctive norms refer to perceptions with regard to significant others’ approval towards displayed behaviors (Chung & Rimal, 2016). Applied to alcohol use, studies indicate that individuals who perceive that their peers consume alcohol more frequently (descriptive norms) and believe that peers approve of consuming alcohol (injunctive norms), increase their own alcohol use (Chung & Rimal, 2016; Neighbors et al., 2007).

Studies in the field of social media effects indicated that social norms and attitudes are parallel mediators for the relation between SNS and alcohol use (Gannon-Loew et al., 2016; Litt & Stock, 2011). Specifically, frequent exposure to alcohol references may alter the perception that peers consume alcohol frequently and approve of consuming alcohol (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016). Additionally, considering that alcohol use is portrayed in a positive context, individuals might associate alcohol with positive outcomes. These perceptions result in more favorable attitudes (Walther et al., 2011). These attitudes and norms, shaped by the individuals’ exposure on SNS, in turn increases the likelihood to use alcohol (Gannon-Loew et al., 2016; Litt & Stock, 2011).

Unsurprisingly in view of its popularity, these studies predominantly focused on Facebook (D’Angelo et al., 2014) or used general measures of SNS (e.g., ‘how often do you encounter pictures referring to alcohol on any SNS?’) (Geusens & Beullens, 2018). However, it is crucial to acknowledge that individuals maintain profiles on multiple SNS simultaneously (Tandoc et al., 2018). Additionally, scholars provided initial evidence for the idea that alcohol references are also omnipresent across multiple platforms including Snapchat, WhatsApp and Instagram, albeit in different forms (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Hendriks, van den Putte & Gebhardt, 2018). Therefore, in line with prior research on alcohol-related social media effects (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Geusens & Beullens, 2018), we expect that exposure to alcohol on these platforms is also related to alcohol use. Moreover, building on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and empirical evidence (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Litt & Stock, 2011), it is expected that norms and attitudes are parallel mediators for the relation between SNS and alcohol use.

H1: Exposure to alcohol references on (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp is positively associated with alcohol use.

H2a: The positive relation between exposure to alcohol references on (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp and alcohol use occurs via more positive attitudes towards alcohol use.

H2b: The positive relation between exposure to alcohol references on (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp and alcohol use occurs via descriptive and injunctive norms towards alcohol use.

Different SNS Features

Despite the fact that alcohol use is shown on different platforms, it is crucial to acknowledge that SNS differ on a multitude of features, resulting in differential alcohol references (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Boyle et al., 2017). At least five dimensions on which SNS differ substantially might impact the nature of alcohol-related posts: (1) the connections between users, (2) perceived privacy, (3) anonymity, (4) persistency, and (5) the focus on aesthetic beauty (Boyd, 2010) (cf. Table 1).

First, SNS vary with regard to connections between individuals (Boyd, 2010; Treem & Leonardi, 2013). These connections consist of numerous social ties with varying strengths including weak and strong ties (Ellison & Vitak, 2015; Piwek & Joinson, 2016). While weak ties refer to connections with distal others (e.g., acquaintances), strong ties represent close connections (e.g., family, friends) (Easley & Kleinberg, 2010). On some SNS (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), users are connected with both strong and weak ties, whereas communication on other SNS is primarily directed towards smaller audiences consisting of strong ties (e.g., Snapchat, WhatsApp) (Lönnqvist & große Deters, 2016; Piwek & Joinson, 2016).

Second, SNS differ regarding the perceived anonymity and privacy (van der Nagel & Frith, 2015). Some SNS only allow the use of real names and require the disclosure of full information (e.g., Facebook) (Taraszow et al., 2010), while using pseudonyms is encouraged on Snapchat and Instagram.

Third, SNS differ with regard to the persistency of messages, which contributes to an allure of privacy and anonymity (Bayer et al., 2016). Whereas messages on some platforms are permanent and remain available until manually deleted (e.g., Facebook) (Treem & Leonardi, 2013), content on ephemeral SNS (e.g., Snapchat) automatically dissolves after some time (Schreiber, 2018; Waddell, 2016).

Lastly, platforms vary considerably with regard to its focus on aesthetic beauty (Schreiber, 2018). Aesthetic beauty refers to the conceptualization of content as creative products whereby individuals strive to constitute visual sense making by framing and cropping pictures and by choosing different perspectives. Resultantly, some platforms are used to share polished and aesthetic content (i.e., Instagram), while others (i.e., Snapchat) are mostly used to share unpolished, more authentic content (Schreiber, 2018).

Alcohol References across different SNS

There are indications to assume that these dimensions are related to differential alcohol references (Boyle et al., 2016, 2017). It has been argued that users either consciously select a specific platform depending on the particular features of this platform and the content they want to share (Tandoc et al., 2018), or adapt their message to what is deemed socially appropriate on a specific platform (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Romo et al., 2017). These decisions lead to differential alcohol portrayals across different platforms (Hendriks, van den Putte & Gebhardt, 2018; Romo et al., 2017).

For instance, individuals are aware that both Instagram and Facebook’s networks consist of multiple, diverse audiences including weak (e.g., peers) and strong ties (e.g., friends, family) with different norms and expectations (Niland et al., 2014; Peluchette & Karl, 2008). As users want to share messages that are acceptable for all of these audiences, they engage in practices of self-censorship on these SNS. Self-censorship refers to a self-presentation strategy in which users consciously select the type of content they want to disclose (Vitak et al., 2015). On these platforms, individuals often choose to share messages that are expected to be socially acceptable and appropriate for multiple audiences (i.e., weak and strong ties) (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Marder et al., 2016; Niland et al., 2014). For alcohol consumption, this implies that Facebook and Instagram users will rather share moderate references in which the use of alcohol is portrayed as a relatively risk-free activity and an inherent part of social occasions (e.g., friends enjoying a drink at a party) (Hendriks, van den Putte, & Gebhardt, 2018; Niland et al., 2014).

Additionally, it has been argued that Instagram’s focus on aesthetic beauty makes it a likely destination for glamorized alcohol portrayals in which only the positive outcomes of alcohol use are shown (Boyle et al., 2017; Hendriks et al., 2018). Thus, when alcohol is shown on Instagram and Facebook, it is frequently portrayed in a positive context in which moderate and socially acceptable forms of alcohol use are shown (Hendriks, et al., 2018).

On the contrary, other platforms are perceived as safer environments to share more consequential and potentially reputation-damaging posts (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Romo et al., 2017). Snapchat and WhatsApp, for instance, are mainly used for private communication with close ties (Piwek & Joinson, 2016; Utz, 2011). These platforms have been found to invoke an allure of privacy among its users, reducing the need for self-censorship (Waddell, 2016). For alcohol references, this implies that these platforms are considered to be safe spaces to share updates referring to less socially accepted and more extreme drinking behaviors such as binge drinking (drinking at least four glasses of alcohol for females, or five for males within two hours) or being drunk (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Boyle et al., 2016). This might especially be the case on Snapchat as this platform offers the possibility to distribute content which dissolves after a limited amount of time (Bayer et al., 2016). Thus, even sharing more potentially reputation-damaging updates, is deemed as relatively risk-free in these environments.

Different SNS, different alcohol-related outcomes

The finding that different SNS are related to different alcohol references has major implications. Specifically, studies in this field either focused on alcohol use or more problematic drinking patterns (e.g., binge drinking) (D’Angelo et al., 2014; Erevik et al., 2017). Yet, considering the vast differences in the nature of alcohol-related references across SNS (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Hendriks, van den Putte & Gebhardt, 2018), not all platforms may be equally important predictors for different forms of alcohol use. From a prevention point of view, however, it is important to know whether some platforms are more strongly linked to more consequential drinking behaviors (e.g., binge drinking) as these particular types of alcohol use often result in more permanent negative health-related outcomes (José et al., 2000; WHO, 2011).Given that risky forms of alcohol consumption (e.g., binge drinking) are more frequently depicted on Snapchat and WhatsApp, as opposed to Facebook and Instagram, this study expects that only exposure to alcohol use on these platforms is associated with emerging adults’ binge drinking.

H3: Exposure to alcohol-related references on (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp is related to binge drinking.

As outlined above, it is expected that these associations can be explained by attitudes and norms. Particularly, individuals observing others engaging in binge drinking on SNS could form the perception that peers frequently engage in binge drinking and would approve of this behavior (Berkowitz, 2004). Additionally, given that also more extreme forms of drinking behavior such as binge drinking are often portrayed as relatively risk-free (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016), exposure to such positive portrayals could be associated with positive attitudes towards binge drinking. Positive attitudes and norms, in turn, have been found to be important indicators of offline drinking behaviors (Cooke et al., 2007; DiGuiseppi et al., 2018). This leads to the assumption that attitudes and norms towards binge drinking are parallel mediators for the relation between exposure to alcohol references on Snapchat and WhatsApp; and binge drinking.

H4a: Exposure to alcohol-related references on (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp is related to binge drinking. The relation between exposure to alcohol references on (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp; and binge drinking is mediated through attitudes towards binge drinking.

H4b: The relation between exposure to alcohol references on (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp; and binge drinking is mediated through descriptive and injunctive norms towards binge drinking.

Method

Sample

Data were collected among 939 Flemish emerging adults. Respondents were recruited via a variety of channels, including different SNS and face-to-face contact. Specifically, messages were sent through the research assistants’ Facebook, Twitter and Instagram account. Additionally, the researchers approached potential participants on different locations popular among students (i.e., student restaurants, study locations). Respondents between the ages of 18 and 25 were asked to participate in a study on leisure activities such as social media and going out. They were assured that their answers remain confidential and anonymous. Upon granting consent, respondents completed a standardized online questionnaire. The study was approved by the institution’s ethical committee.

In total, 939 emerging adults completed the survey but 33 respondents were deleted from the sample because they were younger than 18 or older than 25. Additionally, one case was listwise deleted as the participant did not provide an answer on the majority of questions, leaving a total N of 905 (Mage=20.78; SD=1.88). Females appeared to be overrepresented in our sample (73%). Of the participants, 84.4% were students, 13.3% were employed, 2.3% were doing something else (e.g., stay at home parent).

Measures

Alcohol use

Alcohol use was measured using two items of AUDIT scale (Saunders, et al., 1993). Respondents were asked how frequently they consumed alcohol, with answer possibilities ranging from (0) never to (4) more than four times a week (5-point scale). The second item measured the amount of alcohol consumption on a certain occasion. Responses ranged from (0) I don’t drink to (5) 10 glasses or more. Both items were multiplied to obtain a score representing respondents’ total alcohol consumption (Rehm, 1998; Sobell & Sobell, 2004).

Binge drinking

Binge drinking was measured using the guidelines developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIH, 2003). Respondents were asked ‘during the last 12 months, how often did you consume 4 (women) or 5 (men) glasses of alcohol within a two-hour period?’. Answer possibilities (10-point scale) ranged from (0) never to (9) every day.

Exposure to alcohol references across different SNS

Exposure to alcohol references was measured using a scale adapted from Geusens and Beullens (2018). Participants were asked how often they encountered pictures, videos or text messages referring to alcohol on (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp. Answer possibilities (7-point scale) ranged from (0) never to (6) several times a day. If an individual did not use a certain platform, their answers on the exposure-questions were equaled to (0) never exposed.

Descriptive norms towards alcohol use and binge drinking

Descriptive norms were questioned using the guidelines developed by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010). Descriptive norms towards alcohol use were assessed by three items asking the respondents to estimate how many friends (a) consume at least one full glass of alcohol (b) occasionally drink alcohol and (c) regularly consume alcohol.

Descriptive norms towards binge drinking on the other hand consisted of two items in which participants needed to estimate binge drinking behaviors of friends. Particularly, respondents were asked how often their friends (a) occasionally and (b) regularly consumed 4 (women)/5 (men) glasses of alcohol within two hours. Responses (4-point scale) ranged from (1) none to (4) all of them.

Injunctive norms towards alcohol use and binge drinking

Injunctive norms were measured using an extended version of the scale previously used by Krieger et al. (2016). Injunctive norms towards alcohol use were measured by two items asking the participants to estimate their friends’ approval regarding (a) the use of alcohol and (b) consuming alcohol every weekend. Injunctive norms towards binge drinking on the contrary consisted of one item measuring their friends’ perceived approval towards the consumption of 4 (women) or 5 (men) glasses of alcohol within the timespan of two hours Answer possibilities for both questions ranged from (1) strong disapproval to (7) strong approval.

Attitudes towards alcohol use and binge drinking

Attitudes were assessed using Fishbein and Ajzen’s (2010) guidelines regarding a theory of planned behaviour questionnaire. Participants were asked how they felt about (1) consuming alcohol and (2) binge drinking. As previously used in Geusens, Bigman-Galimore and Beullens (2019), respondents were given 7 adjective pairs including (a) normal-abnormal, (b) harmful-harmless, (c) fun-boring, (d) good-bad, (e) cool-uncool, (f) appropriate-inappropriate and (g) helpful-hindering. Participants were asked to indicate (7-point scale) whether they agreed more with the adjectives on the left (i.e., abnormal, harmful, boring, bad, uncool, inappropriate, hindering) or the ones on the right (i.e., normal, harmless, fun, good, cool, appropriate, helpful). Low scores equal negative attitudes, whereas high scores equal more positive attitudes.

Control variables

Gender (0= male, 1= female), age (open question) and sensation seeking were assessed. Sensation seeking was measured using the 12-item UPPS-P sensation seeking subscale (i.e., personality trait indicating the degree to which individuals seek adventure and excitement) (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Participants were asked to report the extent to which they agreed with 12 statements (e.g., I enjoy taking risks) with responses ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations were calculated using SPSS. Furthermore, AMOS 25 (bootstrapped, 1000 samples, 95% CI) was used to test the measurement and structural equation model. First, in order to gain an accurate representation of reality in which individuals use multiple platforms simultaneously (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp were entered as side-by-side predictors of alcohol use and binge drinking. Additionally, six parallel mediating pathways (i.e. descriptive and injunctive norms towards alcohol use and binge drinking, and attitudes towards alcohol use and binge drinking) were added to the model.

Previous studies have identified sensation seeking (Yanovitzky, 2006), gender and age (Delucchi, Matzger, & Weisner, 2008) as predictors of alcohol use. Specifically, male and younger emerging adults are more likely to consume alcohol (Delucchi et al., 2008). Additionally, emerging adults who are more likely to seek sensation are more sensitive to the positive outcomes of alcohol use and often underestimate the risks associated with consuming alcohol, in turn increasing their alcohol use (Yanovitzky, 2006). Hence, age, gender and sensation seeking were added as control variables.

The model fit was evaluated based on: goodness of fit index (GFI >.95), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI>.80), comparative fit index (CFI >.90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA<.08), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI>.95) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR<.08) (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Measurement model

Sensation seeking, social norms (i.e., injunctive and descriptive norms towards alcohol use and binge drinking) and attitudes (i.e., attitudes towards alcohol use and binge drinking) were specified as latent variables. The injunctive norms towards binge drinking consisted of a single item.

Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the measurement model could be improved (χ2=2582.01, df =507, χ2/df=5.09, p < .001, GFI=.83, AGFI=.80, CFI=.82, TLI= .80; RMSEA=.07; AIC=2758,01; SRMR=.06). Following Kenny’s (2011) guidelines, the model was respecified. The adjective pair ‘harmful- harmless’ from the attitude towards alcohol use scale had a factor loading below .35 and was dropped. The same adjective pair was deleted from the attitude towards binge drinking scale in order to keep both measurements consistent. This change resulted in improvement of the fit (χ2=1911; df=444, χ2/df=4.03, p < .001, GFI=.88, AGFI=.85, CFI=.86, TLI=.85; RMSEA=.06; AIC=2079; SRMR=.05).

Next, based on the modification indices, several error loadings were covaried. In the attitude towards binge drinking scale, we covaried the adjective pairs ‘good – bad’ and ‘appropriate – inappropriate’ (r=.42; p < .001). Additionally, the error loadings of the item ‘helpful – hindering’ from the attitudes towards alcohol use and attitudes towards binge drinking scale had to be covaried (r=.36; p < .001). Furthermore, from the descriptive norms towards alcohol use scale, we had to covary two items (i.e., consumption of at least one full glass of alcohol – the occasional consumption of alcohol) (r=.33; p < .001). Finally, two items from the sensation seeking scale were covaried (i.e., water skiing - skiing) (r=.28; p < .001). These changes resulted in an improved model fit (χ2=1507.78, df=440, χ2/df=3.43, p < .001; GFI=.90; AGFI=.88; CFI=.90; TLI=.89; RMSEA=.05; AIC=1683.78; SRMR=.05).

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 gives an overview of the descriptive statistics. Respondents indicated to frequently encounter alcohol references across different SNS. On average, they see these references about once a month on WhatsApp (M=.82;SD=1.34), several times a month on Snapchat (M=2.72; SD=1.85) and Instagram (M=2.59;SD=1.58), and about once a week on Facebook (M=3.28;SD=1.52).

Of the emerging adults in the sample, 6.4% indicated to never consume alcohol, 15.4% less than once a month, 49.4% two to four times a month, 27.4% two to three times a week and only 1.4% indicated to consume alcohol more than 4 times a week. On average, the respondents in our sample typically consumed 3 or 4 glasses of alcohol on a typical drinking day (M=2.17; SD=1.27). Moreover, 24.4% of the emerging adults in the sample indicated to never engage in binge drinking (consuming at least 4 glasses for women and 5 for men within two hours) and 44.6% at least once a month.

Additionally, the participants in the sample reported slightly negative attitudes towards binge drinking (M=3.24; SD=.95), but showed positive attitudes towards alcohol use (M=4.27; SD=.71). Furthermore, participants believed that many of their friends regularly drink alcohol (M=3.45; SD=.47), engage in binge drinking (M=2.56; SD=.70), and would approve of both consuming alcohol (M=4.76; SD=1.17) and binge drinking (M=3.86; SD=1.46).

Finally, zero order correlations (cf. Table 2) indicated that all platforms are significantly, positively related to alcohol use, binge drinking, attitudes (alcohol use and binge drinking), and descriptive and injunctive norms (alcohol use and binge drinking).

Testing the hypotheses

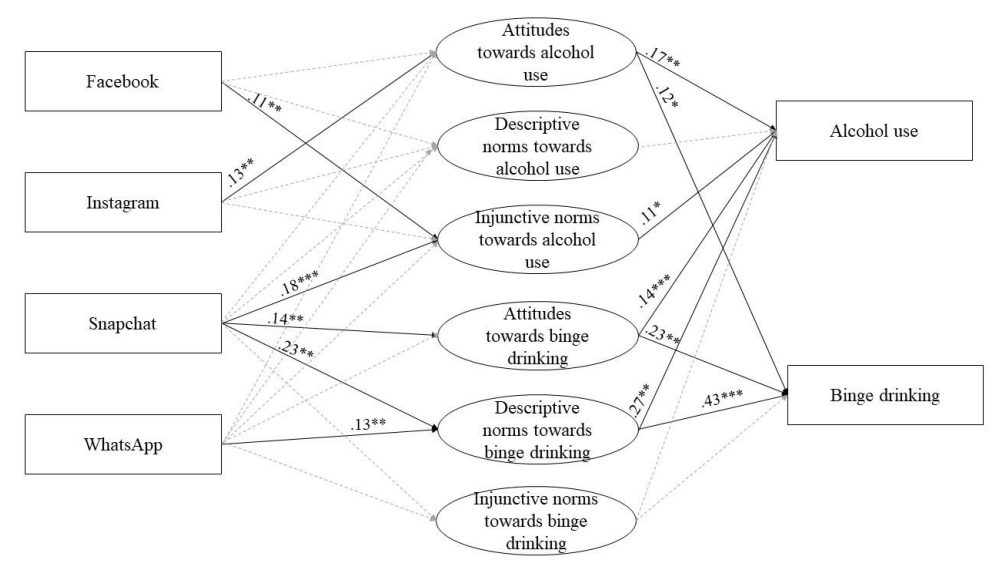

In order to investigate whether exposure to alcohol references on (a) Facebook, (b) Instagram, (c) Snapchat and (d) WhatsApp are related to alcohol use and binge drinking via attitudes (alcohol use - binge drinking), and descriptive and injunctive norms (alcohol use - binge drinking), one bootstrapped (1000 samples) structural equation model was generated (see Figure 1). Fit indices indicated that the model fitted the data acceptably (χ2=1916.45; df=641; χ2/df=2.99; p < .001; GFI=.90; AGFI=.87; CFI=.91; TLI=.88; RMSEA=.05; SRMR=.05).

Structural equation model (Bootstrapped, 1000 samples) for the indirect relationship between exposure to alcohol references across different SNS, social norms (descriptive and injunctive norms towards alcohol use – binge drinking), attitudes (alcohol use – binge drinking); alcohol use and binge drinking (N=905).

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Controlled for gender, age and sensation seeking.

Each arrow displays the standardized direct effects. The grey arrows display non-significant results. Correlations and direct effects between variables are not displayed for clarity.

The direct and indirect relation between SNS and alcohol use

In line with the first hypothesis, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp are positively related to the consumption of alcohol (cf. Table 3).

Overview of bootstrapped (1000 samples) standardized total, direct and indirect effects of the relation between exposure to alcohol on SNS and alcohol use

Furthermore, it appears that norms and attitudes towards alcohol use are significant mediators for these relations (H2). Specifically, exposure to alcohol references on Facebook and Snapchat is positively associated with alcohol use via social norms alcohol use. The positive relation between exposure to alcohol on Instagram and alcohol use occurs via a change in attitudes towards alcohol use. Additionally, contrary to our expectations, WhatsApp was only directly related to alcohol use and thus did not operate through norms or attitudes. Thus, only partial support was found for hypothesis 2.

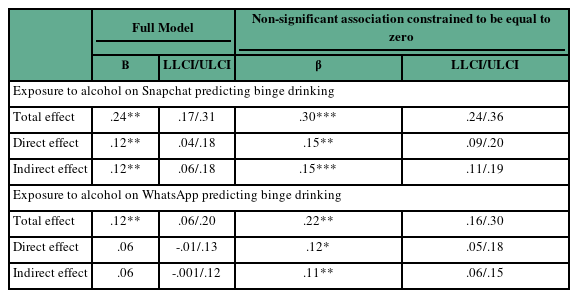

The direct and indirect relation between SNS and binge drinking

In confirmation of hypothesis 3 (Cf. Figure 1, Table 4), the findings indicate a positive association between exposure to Snapchat and WhatsApp on the one hand, and binge drinking on the other hand. Additionally, exposure to alcohol on Instagram and Facebook is not significantly associated with binge drinking.

Overview of bootstrapped (1000 samples) standardized total, direct and indirect effects of the relation between exposure to alcohol and binge drinking

Hypothesis 4 was only partly supported: Exposure to alcohol on Snapchat is positively related to binge drinking via attitudes and norms towards binge drinking, while WhatsApp only seems to operate via norms towards binge drinking.

Discussion

Recently, scholars have provided evidence for a positive relation between SNS and alcohol-related cognitions and behaviors (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Curtis et al., 2018). However, these studies show two fundamental shortcomings. Particularly, most research solely focused on the effects of Facebook or treated social media as one homogenous construct (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Geusens and Beullens, 2018). Yet alcohol references appear to be prevalent across multiple SNS platforms, albeit in different forms (Boyle et al., 2017); and individuals often maintain multiple SNS profiles simultaneously (Tandoc et al., 2018). This study is among the first to investigate Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and WhatsApp as side-by-side predictors of alcohol use.

Furthermore, research on alcohol-related social media effects has interchangeably examined the effects of SNS on alcohol use and problematic drinking patterns (e.g., binge drinking) without distinguishing between both outcomes (Curtis et al., 2018). Yet, given that SNS differ on a multitude of dimensions (e.g., connections, persistency, anonymity) (Treem & Leonardi, 2013), resulting in notable differences with regard to how alcohol use is portrayed (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Peluchette & Karl, 2008), it is conceivable to expect that they are related to different alcohol-related outcomes. Specifically, past studies indicated that Snapchat and WhatsApp are more likely destinations for the sharing of more risky drinking references, whereas Facebook and Instagram tend to be home to moderate and socially acceptable alcohol references (Hendriks, van den Putte, & Gebhardt, 2018). Consequently, this study hypothesized that exposure to Snapchat and WhatsApp would be associated with binge drinking, while exposure to alcohol on Facebook and Instagram would not.

Extending prior research, our results demonstrate that Facebook is not the only platform related to alcohol use. Instead, our results suggest that exposure to alcohol references on Snapchat, Instagram and WhatsApp are associated with alcohol use as well. Although these platforms have received far less research attention, a recent longitudinal study from Boyle et al. (2016) also indicated that exposure to peers’ alcohol references on Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram predicted alcohol use six months later. As the use of Snapchat, Instagram and WhatsApp has skyrocketed among emerging adults (Vanhaelewyn & De Marez, 2018), we recommend future research to broaden its scope and examine the uses and effects of these platforms too.

This is especially relevant because the results of the current study indicated that Snapchat and WhatsApp – as opposed to Facebook and Instagram – are positively associated with more consequential forms of drinking namely binge drinking (i.e., consuming at least four glasses for women and five for men within two hours). This can be explained by the fact that there are important differences with regard to how alcohol use is portrayed across different platforms (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Boyle et al., 2017). Specifically, studies indicate that more problematic, less socially acceptable drinking patterns (i.e., binge drinking) are regularly shown on Snapchat and WhatsApp (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016), whereas more moderate, socially acceptable forms of drinking are portrayed on Facebook and Instagram (Boyle et al., 2017). Although past studies have reported that overall SNS use is associated with problematic forms of drinking behavior (Geusens & Beullens, 2018), the results of the current study indicate that it is important to take multiple SNS into account. Indeed, whereas zero-order correlations pointed toward positive associations between the uses of all platforms and binge drinking, only Snapchat and WhatsApp appeared to predict binge drinking when all SNS were taken into account. This seems to indicate that the association between Facebook and Instagram on the one hand and binge drinking on the other hand is spurious and in fact explained by exposure to alcohol on Snapchat and WhatsApp.

Apart from the differences in the nature of alcohol references between platforms, individuals’ motivations to share and the time at which alcohol references are shared may be equally important. In general, all platforms are used after drinking events in order to share memories following a fun night out (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Bayer et al., 2016). Nevertheless, Instagram and Facebook are perceived as the most important platforms to memorialize such drinking events. On the other hand, it has been shown that WhatsApp is predominantly used prior to drinking events (e.g., to invite friends to a party) and Snapchat during drinking events (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Bayer et al., 2016). The specific time at which a message is shared might change the motivation to share, resulting in different content and different effects. We recommend that future studies examine the associations between multiple SNS and alcohol use longitudinally and thereby take individuals’ motivations to share and the timeframe in which they are shared into account.

Third, in line with previous studies, social norms and attitudes appear to be central mechanisms explaining the relation between SNS and different forms of alcohol use (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016; Geusens & Beullens, 2018). However, not all platforms seem to operate via the same mechanisms. Specifically, Facebook, Snapchat and WhatsApp appear to operate via social norms whereas Instagram did not. One possible explanation lies in the proximity of the audience with whom individuals connect. In line with the social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) and the social impact theory (Latané, 1981), it is conceivable to expect that social norms would be more strongly influenced by proximal others than distal others. Whereas individuals predominantly connect with offline connections on Facebook, Snapchat, and WhatsApp; Instagram is the only platform on which individuals also regularly engage with strangers (e.g., celebrities)(Lee et al., 2015). However, future research is needed to confirm these assumptions.

Additionally, the results indicate that Instagram and Snapchat are the only platforms related to positive attitudes. The type of content that is distributed on these platforms could explain this finding. Specifically, Instagram and Snapchat are image-based platforms, as opposed to Facebook and WhatsApp (Schreiber, 2018). Image-based platforms offer extensive photographic enhancement possibilities (i.e., filters) in order to retouch pictures (Schreiber, 2018) and to portray alcohol in a certain way. Previous studies already assumed that such positive alcohol references enhance positive attitudes (Geusens & Beullens, 2018) due to the fact that individuals associate alcohol with positive outcomes (Walther et al., 2011). Considering that alcohol pictures on Instagram appear to be glamorous (Boyle et al., 2017), positive attitudes towards alcohol use could be formed. Pictures on Snapchat on the other hand portray more extreme forms of alcohol use (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Utz et al., 2015). However, it is likely that such portrayals are still presented in a positive way in which alcohol use is an intrinsic part of having fun with friends (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016), resulting in positive attitudes towards binge drinking. Studies in other fields seem to confirm these assumptions. Specifically, scholars indicated that visual media are easier to interpret due to its richness in visual cues and therefore receive more affective evaluations (e.g., attitudes) compared to textual media (Jeong & Choi, 2008; Lee & Ho, 2018).

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some shortcomings. First, we relied on self-reports, potentially resulting in the over- or under-reporting of alcohol use. Yet, self-reports appear to be a valid approach to measure alcohol use (Del Boca & Darkes, 2003).

Furthermore, the operationalization of some of the measures could be improved. For instance, an imbalance in the number of items measuring social norms towards alcohol use on the one hand and binge drinking on the other hand exists. We recommend future studies to rely on social norms scales in which different forms of alcohol use are measured through multiple items. Additionally, we opted for single-item measures to operationalize exposure across different SNS. Although single-item measures often lack construct validity and reliability, the use of such measures is justified if the construct is unidimensional and perceived similarly by all participants (e.g., four SNS) (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, 2009).

Third, we argued that platforms differ on various dimensions resulting in different alcohol references (extreme references on Snapchat, WhatsApp). Though several studies provided evidence for this idea (Atkinson & Sumnall, 2016; Boyle et al., 2017; Hendriks et al., 2018), we did not measure the participants’ awareness or use of these features, nor their exposure to different types of alcohol references. In addition, we only included a limited number of predictors of emerging adults’ drinking behaviors (i.e., norms, attitudes, SNS, gender, age, sensation seeking). It should be acknowledged, however, that individuals’ alcohol use is often influenced by a variety of factors (e.g., religion, parental monitoring, availability of alcoholic beverages) (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014; Rosiers et al., 2018).

Another limitation is the representativeness of the sample. This can be attributed to the variety of recruiting strategies that were used. Though convenience sampling is not uncommon in this type of research (Beullens & Vandenbosch, 2016), the patterns in alcohol behaviors appear to be largely representative when comparing it to national representative samples (De Bruyn et al., 2018; Van Damme et al., 2018). Additionally, the sample consisted of Flemish emerging adults only. However, intercultural differences in drinking behaviors exist. Specifically, Belgium is a country with a relative tolerant alcohol policy allowing individuals to buy alcoholic beverages from the age of 16. Resultantly, cross-cultural studies are necessary to investigate whether our results can be applied to other countries.

Finally, we opted for a cross-sectional design preventing us from making causal inferences. In line with Slater’s (2007) reinforcing spirals model, it is likely that individuals seek out alcohol-related content congruent with their own cognitions and behaviors resulting in the reinforcement of previous alcohol-related cognitions and behaviors (Geusens & Beullens, 2017; Slater, 2007) (Geusens and Beullens, 2017). In order to get insight in the temporal order, longitudinal studies are required.

Implications

Despite its limitations, the current study has important implications. First, this study provides a more nuanced understanding of how different platforms are associated with differential forms of alcohol use (alcohol use – binge drinking). Though all platforms are related with alcohol use, Snapchat and WhatsApp also play a more particular role in problematic drinking patterns. These insights might be useful for other domains as well. Specifically, it may be possible that platform differences exist in other types of risk behaviors (e.g., platform differences in sexual risk behavior) (Poltash, 2013). As such, the results of this study not only refine our insights in the relationship between SNS and alcohol use, they also open an avenue for new research endeavors that scrutinize the roles of different SNS in other risk behaviors.

Apart from theoretical implications, this study provides new insights for intervention initiatives aimed at reducing harmful alcohol use. Specifically, this study demonstrates the importance of focusing on emerging SNS as they are associated with more consequential forms of alcohol use. Resultantly, social media-based interventions should not only focus on Facebook (Ridout & Campbell, 2014), but also on other platforms.

Notes

Funding Details

This work was supported by the Research Foundations Flanders (FWO) under Grant [11G2420N]. In addition, the first author is funded by PhD fellowship from the same foundation. We thankfully acknowledge the foundations’ support.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mister Luca De Ceuster and Miss Veerle Verlinden for their contribution in the data collection phase.