“The mask is not for you”: a framing analysis of pro- and anti-mask sentiment on Twitter

Article information

Abstract

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread adoption of facemasks has been recognized as a low-cost, simple public health intervention that can reduce the transmission of the virus. However, early in the pandemic significant public opposition emerged in the U.S. and other parts of the world. So-called “anti-maskers” argue that COVID-19 is a hoax or the threat is overblown, that facemasks are ineffective, or that mask mandates infringe on personal rights and freedoms. Social media platforms can play an important role in shaping public sentiment about health issues, as well as circulating harmful misinformation. Researchers can also study social media data to better understand public perceptions and dominant discourses. This study examines four prominent mask-related hashtags on Twitter across three different time periods early in the pandemic. A content analysis of these tweets was used to investigate pro- and anti-mask wearing sentiment, the motivations behind these beliefs, the rhetorical strategies and themes present in these communications, and changes over time. Of the 600 tweets collected, 440 were pro-mask wearing, 134 were anti-mask wearing, and 26 did not declare a position. Pro-mask tweets used evidence at a rate of 28%, while anti-mask tweets used evidence at a rate of 16%. The most common motivation for a pro-mask position was mask-wearing as a civic duty, and the most common motivation for an anti-mask position was standing up to government tyranny. There were 68 tweets that expressed distrust in institutions, 97% of which were anti-mask, 44% mentioned a conspiracy theory while only 18% used evidence to support their position. It was found that mask sentiment on Twitter encompasses a variety of themes, worldviews, and rationales. Public health messaging must go beyond information transmission, and account for the complexity of the social, political, and economic factors which influence belief and behavior.

Introduction

Throughout the spring and summer of 2020, there was extensive news coverage, social media debate, and public health messaging about mask wearing and COVID-19 (Godoy, 2020; Lopez, 2020). At the beginning of the pandemic in March and April, much of the debate and uncertainty was focused on whether face masks protect the wearer, or if a person who is positive for COVID-19 is less likely to infect others by wearing a mask (Esposito et al., 2020; Lopez, 2020). There was concern about global shortages of personal protective equipment for frontline healthcare workers (Esposito et al., 2020) amidst reports of members of the public stockpiling personal protective equipment, and turmoil in the United States around the production and distribution of masks (Nguyen, 2020). Some commentators believed that if the public were advised to wear face masks, people could accidentally infect themselves through improper donning and doffing of the mask, exacerbating rather than reducing overall spread of the virus (Howard, 2020; Matuschek et al., 2020).

By May 2020, the scientific consensus supported the idea that mask wearing can effectively limit the spread of COVID-19, largely by keeping infectious particles inside the mask and thus protecting others from becoming infected (Howard et al., 2020). Nonetheless, as health experts around the world began issuing formal recommendations for mask wearing, large segments of the public appeared to express confusion about this changing stance or “about-face” (Urback, 2020).

Even in May 2020, several months after the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (WHO, 2020), there were still questions and gaps in the evidence base about whether cloth masks protect the people wearing them, and the degree of protection offered by different mask materials. There were no studies specifically examining the utility of cloth masks in the community (Clase et al., 2020). However, as Canada's chief public health officer Dr. Theresa Tam explained in April, although the science was not certain, encouraging members of the public to wear masks seemed to be “a sensible thing to do” based on emerging reports and studies (Tasker, 2020).

Indeed, COVID-19 has proven to be infectious before the onset of symptoms, and asymptomatic spread has been documented (Zhao et al., 2020). Masks are now widely viewed by the medical and scientific communities as valuable tools that will help reduce the spread of COVID-19, especially as communities around the world re-open and in contexts where physical distancing is difficult or not possible. Yet as many countries re-open and economies start back up, face masks have continued to be surrounded in controversy and public debate. In the U.S. and other parts of the world, mask wearing has become a political statement. Some of the so-called “anti-maskers” refute the growing evidence base that widespread adoption of mask-wearing in public can limit the spread of COVID-19. Others contend that mask mandates – laws or regulations that enforce mask-wearing in public spaces – are “authoritarian” and infringe on personal rights and freedoms (Stewart, 2020).

On September 12th, 2020, several thousand people gathered in downtown Montreal to protest the provincial government's response to the pandemic. Protestors held signs that indicated support for conspiracy theories, such as a supposed link between COVID-19 and the 5G cellular network, or perceived corruption at the World Health Organization (Montpetit & MacFarlane, 2020). This protest fell on the same day that new police powers came into effect in the province, giving officers the authority to fine anyone not wearing a mask inside a public building. Other countries have seen similar protests motivated by anti-mask sentiment or opposition to other public health measures (Kim, 2020).

This opposition to masking is not uniform: public sentiment around masking appears to vary between different countries and may be connected to political affiliation (Alberga et al., 2020; Pew, 2020). In other words, public sentiment on mask wearing eludes easy characterizations. Much like the underlying evidence on the effectiveness of mask wearing as a public health intervention to contain COVID-19, public sentiment has seemingly evolved over time. Some segments of the public may be opposed to masking based on distrust of health authorities and other institutions, whereas others express doubt about the efficacy of facemasks, or appear to subscribe to conspiracy theories that state COVID-19 is a “hoax” or that the seriousness of the virus has been overblown (Stewart, 2020). Conversely, many Canadians have expressed disappointment in government leaders and health agencies for not recommending widespread masking earlier in the pandemic (Mahal, 2020).

In a short interval of time, competing narratives and explanations have emerged about the political motivations behind some “anti-masker” beliefs, and some research has explored the dynamics of misinformation spreading online (Kouzy et al., 2020) and the effectiveness of different public health messaging and strategies (Jordan et al., 2020).

Social media platforms such as Twitter have been viewed as sites that have the potential to shape public perceptions by exposing people to different messages and communities. In addition to possibly influencing beliefs, such platforms can also provide valuable insight into public sentiment and in turn, help develop more effective public health messaging and intervention strategies (Keim-Malpass et al., 2017; Scanfeld et al., 2010). This study attempts to better understand the public sentiment around mask-wearing and the dynamics of (mis)information spread on social media. We examined several prominent mask-related hashtags over the course of three months. Public perception is important because it reflects concerns, beliefs, and values, and identifies the information required to address gaps in understanding. Further, awareness of public opinion on health topics helps ensure that services and policies are aligned with the beliefs and priorities of the general public (Giles & Adams, 2015). This study documents public perceptions and beliefs surrounding mask-wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic and provides information about the nature and prevalence of different messaging strategies and the stated motivations for supporting or opposing mask-wearing.

Literature Review

Past research has extensively documented the spread of health-related misinformation, sensationalism, and public fear (Sell et al., 2020), noting the presence of underlying social anxieties concerning expanding transportation networks, mass immigration, the environment, and distrust of governmental authority (Tomes, 2000). Much work has described the sensationalist rhetoric and misinformation surrounding, for example, the 2002 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak (Washer, 2004), Swine Flu epidemic (Klemm et al., 2016), and Ebola crisis (SteelFisher et al., 2015; Towers et al., 2015). In other words, media platforms are often viewed as sites that circulate and reinforce misinformation – whether because public perceptions of risk are susceptible to social and cultural factors that can lead to conflicts and confusion (Pidgeon et al., 2003; Slovic, 1987), or because social media conversations and news coverage is characterized by fear-mongering, sensationalism, and the de-contextualization of scientific information (SteelFisher et al., 2015; Towers et al., 2015; Washer, 2004), supposedly demonstrating the capacity for these media platforms to impact (or perhaps interfere with) public perceptions (Boyd et al., 2009).

This line of argument in some ways follows a simple transmission model of communication, with the assumption that media conversations and depictions of disease and healthcare directly influence public perceptions. Indeed, much of this research is overly preoccupied with “representations of disease’”issues, doing little to question the sites of mediation, forms of expertise and institutions, or problematizing the definitions of “disease” and “media.” Further, although there is increased attention towards institutions and sites of mediation beyond the news media, the literature on the mediation of diseases largely still subscribes to “media effects” assumptions. Various texts are read and inaccuracies, misinformation, narrative frames, and so forth are identified, typically gesturing towards an unreliable media (whether this is news, social, or entertainment) that obscures scientific fact, instilling and reproducing fear and ignorance in a susceptible, uncritical public. These kinds of assumptions, which focus on these media platforms as the sole or primary culprits, overlook other potential sources of misinformation. It positions the public as a passive audience that depends on receiving information from objective, infallible scientific and government authorities, and the only role of the media is to accurately translate or transmit this information. Further, the public communication of science is viewed as primarily occurring in the realm of the press, overlooking other sources of information, storytelling, and influence. Past research has made connections between media consumption and health-related beliefs (Allington et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2018). Yet it is important to problematize notions of medical authority, mediation, and disease, and to avoid oversimplifying the potential role of media depictions of disease on shaping public perceptions.

Much of the literature on the mediation of disease is characterized by these limited or outdated frameworks, which could arguably be traced back to literature from the 1980s and 90s that analyzed media coverage and public understandings of HIV and AIDS. Broadly speaking, much of this research was focused on representations of people with HIV/AIDS in the news, connecting these depictions to larger societal responses surrounding the disease or “general notions of morality and .... medicine, health and illness” (Lupton, 1994b, p.37). Kreps et al. (1998) explored the development and history of the field of health communication, noting that many of these communication scholars worked on health promotion campaigns that sought to minimize public risks of contracting HIV/AIDS, as well as heart disease and cancer. This orientation towards health promotion was reflected in their scholarly work on HIV/AIDS, which typically considered the flow of health information through mediated channels and the depiction of diseases and health care in popular media.

More recent work has, notably, challenged some of these outdated, narrow conceptions of the public and sources of health-related information, or troubled distinctions between “risk” and “fear” (for examples, see: Abraham, 2011; Greenberg & Rainford, 2014; Levina, 2015; Muntean, 2009), or perhaps expanded the scope of analysis to other platforms and sources of disease information (for examples, see: Gerlach & Hamilton, 2014; Levina, 2015; Seltzer et al., 2015; Stellefson et al., 2014; Wonser & Boyns, 2016; Young et al., 2013). As supported by more recent science communication work on issues such as vaccine hesitancy, the public is not a passive audience with beliefs that are entirely determined by exposure to accurate (or inaccurate) information (Nyhan & Reifler, 2015).

More recent work problematizes this characterization of an ignorant or “panicky” public. Although Davis et al. (2014) note the prevalence of sensationalist depictions of contagious diseases in the media, they argue that the public’s engagement with and understanding of these images and representations is more complex than most critiques of the media would suggest, which typically contend that “the general public is a problem for efforts to manage global problems such as pandemic influenza” (513). Through focus groups and interviews with members of the public, Davis et al. (2014) found that most respondents were aware of media sensationalism and the amplification of risk.

This does not mean that mediatized discourses around health issues are irrelevant or unimportant, but rather, that public sentiment cannot be understood through models that focus exclusively on information transmission. Muntean (2009) posits that “social and political conceptual frameworks” work to discursively construct pandemic fear (199). Despite there being fundamental differences between, for example, viruses and bacteria, or between disease outbreaks and hazards such as radiation or terrorism, boundaries between these distinct issues are blurred through “epistemological influences” such as the 9/11 attack (199). In other words, disease threat may be socially constructed according to prominent events or “scripts” in the public consciousness: formative, “archetypal” events (such as the 9/11 attacks) provide frameworks that position government responses and public conceptions. Indeed, Ungar (1998) argued that diseases are constructed and understood through “interpretive packages” made up of “metaphors, exemplars, stories, visual images, moral appeals and other symbolic devices” (39).

Similarly, Serlin (2012) notes how public health is defined not only by imagery “drawn from biomedicine but also from the vast web of media forms with which public health intersects” (xxiii) and Wald’s (2010) conception of “outbreak narratives” demonstrates how the meaning of disease is articulated through shared understandings – tropes, storylines, and practices – that come about through past disease events and shape future health outcomes by stigmatizing certain groups, affecting economies, and influencing “how both scientists and the lay public understand the nature and consequences of infection” (3).

This study attempts to draw on this more nuanced understanding of public perceptions and media, in which the construction and articulation of health issues occur through a larger social imaginary that draws upon (and reproduces) certain narratives, ideologies, and practices. Disease is not just depicted or represented, something that is easily reduced to media imagery or frames, but rather is something constructed in the cultural imagination, informed by history, geography, and politics (Bashford & Hooker, 2001). Through this understanding of public perceptions and media, we can view social media platforms such as Twitter as sites where health and risk-related concepts are both represented and constructed, according to complex forms of patterning that emerge from a shared cultural repository of past events, media depictions, institutional actions, and so forth.

There is increasing attention on how social media can serve as a source of health-related (mis)information (e.g., Dyar et al., 2014; Fung et al., 2014; Mollema et al., 2015; Nagpal et al., 2015; Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2015; Towers et al., 2015). This research often argues that being exposed to other social media users’ expressions of fear can lead to misguided or exaggerated concerns (see Fung et al., 2014; Nagpal et al., 2015), or shows how prominent health crises or exposure to sensationalized news coverage may lead to bursts of activity online (for examples, see Dyar et al., 2014; Mollema et al., 2015; Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2015; Towers et al., 2015). Some of this research (for example, Dyar et al, 2014) presumes that a brief increase in online activity is a meaningful representation of societal engagement on a health issue, which may be overstating the results. Nonetheless, social media conversations may contribute to heightened public perceptions of risk, as platforms such as Twitter allow for the proliferation of (and exposure to) messages containing anxiety and fear, amplifying concerns and alarm (Fung et al., 2014). Other work has considered how organizations such as the CDC can use social media platforms to attempt to manage uncertainty during times of crisis. In an analysis of CDC tweets during the 2014 Ebola crisis, Dalrymple et al. (2016) found that there was an emphasis on providing background information and establishing credibility. Certain events, however, such as the transmission of Ebola from a patient to a nurse, can “serve as bifurcations or ‘flash points of change’ that require rapid redirection on social media” (457).

In response to concerns about misinformation propagating through social media, companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google have implemented changes to their policies, though information about the effectiveness of these efforts is limited (Anderson & Rainie, 2017; Levin, 2018, 2019). Past research on health-related issues and social media has called for the use of these platforms to help educate the public and challenge incorrect beliefs (Chou et al., 2009; Gesser-Edelsburg et al., 2018; Korda & Itani, 2013; Scanfeld et al., 2010).

Social media discourse may reveal public beliefs or misconceptions (Signorini et al., 2011), yet there are barriers to leveraging social media as a tool to educate the public (Bhattacharya et al., 2014; Heldman et al., 2013; Neiger et al., 2013). For example, so-called “filter bubbles” describe the isolation caused by algorithms and self-sorting into communities where users mostly encounter content that conforms to their pre-existing beliefs (Bozdag & van den Hoven, 2015; Pariser, 2011). However, some research challenges the existence of filter bubbles and their significance in society, rejecting the idea of filter bubbles from both a psychological and technical point of view (Dahlgren, 2021). Bruns contends that the focus on filter bubbles is merely an attempt to “absolve ourselves of the mess we are in by simply blaming technology” (2019, 7). Further, countering misinformation by attempting to circulate and expose people to accurate information harkens back to the “deficit approach” to science and health communication, which is now viewed as an ineffective and oversimplified model (Simis et al., 2016). Indeed, it has been found that mere exposure to corrective information does not necessarily persuade people to change their views on scientific and health issues (e.g. Corner et al., 2012; Nyhan & Reifler, 2015).

Past research has explored “hashtag activism” and the different actors and their narrative strategies for constructing, deconstructing, or circulating discourses (Wonneberger et al., 2020). A study on hashtags and online discourse around animal rights and seal hunts in Canada found that Twitter has failed “to generate a climate of genuine debate” as such platforms serve as echo chambers (Knezevic et al., 2018).

Despite the apparent ineffectiveness of the deficit model, public perceptions still matter: support for conspiracy theories and widespread misinformation can prolong disease outbreaks and hinder policy (Earnshaw et al., 2020). Understanding the themes and patterns of social media conversations can help reveal the interpretive systems that people are using (and circulating) as they engage with issues such as mask-wearing, and perhaps allow for more effective public health messaging that goes beyond information transmission and targets issues of trust, disenfranchisement, and political polarization.

Other work has examined public sentiment toward public health measures during COVID-19, using both surveys and Twitter data. Tsao et al (2022) collected English language Tweets from Ontario, Canada, and explored public sentiment about issues and measures including vaccination, lockdowns, and the impacts of COVID-19 on business; they found a slightly positive sentiment on average during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario. A study on Twitter data and mask-wearing found that most of the mask Tweets were in favor or neutral towards mask-wearing, while a smaller percentage of Tweets were against mask-wearing (Cotfas et al., 2021). Other work used surveys to characterize attitudes toward mask-wearing and found that those who did not wear masks tended to have an aversion to being forced to wear masks and believe that masks are ineffective in preventing COVID-19 (Taylor & Asmundson, 2021). Using an online survey, Esmaeilzadeh (2022) identified and categorized the critical concerns of wearing masks, and found that discomfort barriers, external factors such as political beliefs, and usability issues are the primary concern categories. Another study that used Twitter data examined COVID-19 vaccine-related tweets to characterize the topics, themes, and sentiments of public Twitter users and found evidence of broader themes including vaccination policy, vaccine hesitancy, and postvaccination symptoms and effects. It was found that sentiment scores were negative for the topics “postvaccination symptoms and side effects,” but consistent positive sentiment scores were found for topics such as “vaccine efficacy,” “clinical trials and approvals,” and “gratitude toward health care workers” (Chandrasekaran et al., 2022). A similar study from fall 2021 that collected 300,000 geotagged Tweets about COVID-19 vaccines in the United States found an increasing trend in positive sentiment alongside a decrease in negative sentiment, reflecting rising confidence and anticipation towards vaccines. This suggested that the public trusts the vaccine and “critical social or international events or announcements by political leaders and authorities may have potential impacts on public opinion towards vaccines” (Hu et al., 2021).

Methods

As one of the most popular social media platforms in the world, Twitter provides rich data that can be used to understand public sentiment and discourses around an issue such as mask-wearing. Twitter has also increasingly been used to disseminate public health information, and to acquire real-time health data (Medford et al, 2020). Other studies have drawn on Twitter data to examine the spread of misinformation during the COVID crisis (Bolsover & Tizon, 2020; Kouzy et al., 2020), analyze discussions of COVID-19 conspiracy theories (Ahmed et al., 2020), and assess the credibility and prevalence of information relating to the pandemic (Yang et al., 2020).

Pei and Mehta (2020) performed a quantitative sentiment analysis on Tweets with racist hashtags about COVID-19, such as #Chinesevirus and #Chinavirus, across several stages of the pandemic. This kind of work provides valuable information about the kind of sentiment (positive or negative) associated with different hashtags, and how this sentiment might shift over time. Our study focuses on the issue of mask-wearing, and in contrast to studies that use automated sentiment analysis on larger datasets, our manual coding methodology (detailed below) goes beyond classifications of positive or negative sentiment and provides more detail about the kinds of framing and themes that are present, and thus a more granular understanding of how discourses around mask-wearing are being constructed and circulated.

This study draws on framing theory, which refers to how information is packaged and presented to the public; information is placed within certain contexts to encourage or discourage particular interpretations, exerting an influence over how people perceive reality (Tewksbury & Scheufele, 2009). In other words, “Framing refers to the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue” (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 104). According to Entman (1993), framing is an organizational and communication process in which some aspects of reality are given greater emphasis and messages can influence the perceptions of individuals. We applied framing theory to the collected Tweets in order to see how mask-wearing was being framed – for example, as a form of civic duty, to protect personal safety, or as an infringement on individual freedoms. This allowed us to understand the discourse around mask-wearing during specific time periods, and therefore how the wider public may have been perceiving the issue.

Data Collection

Several of the most popular mask-related hashtags were selected for study, including #WearaMask, #Mask4All, #Mask, and #NoMask. English-language tweets that contained any of these hashtags were collected from three different intervals of time: June 1st to 15th, July 1st to 15th, and August 1st to 15th 2020. These three different time periods were selected to explore whether sentiment changed over time. The months of June, July, and August were chosen because this period included several important developments for mask-wearing. The World Health Organization changed its advice on face masks at the beginning of June, saying they should be worn in public where social distancing is not possible to help stop the spread of coronavirus (reference). Throughout July and August, many regions began enforcing mask-wearing mandates and laws.

Through Twitter API for Python, we extracted 1,000 tweets for each hashtag and time period, for a total of 12,000 tweets. Following data collection, all identifying information was removed, including usernames, bios, and location, to protect the anonymity of the authors. This de-identification of data was completed before coding began.

This larger dataset of 12,000 tweets is being used for another project that is comparing several automated sentiment analysis tools. For this study, a random sub-sample was selected for coding. After exporting the data to Excel, each tweet was randomly assigned a numerical value, and researchers then gleaned a random sample of the data by collecting the first 50 tweets from each hashtag and time period, for a total of 600 tweets. Irrelevant and non-English tweets were removed, as well as tweets that exclusively contained external links.

Coding procedure

A codebook was used that was both inductive and preconstructed. Prior to examining the data, the co-authors met and developed a list of potential codes based on knowledge of the pandemic and previous literature. The first 25% of tweets from each hashtag and time period were then examined. New codes were inductively generated from this initial examination of the data, and preconstructed codes were removed if they were not prevalent in the data. The final codebook is provided as an appendix. To ensure consistency, only one of the researchers coded the data from the random sample.

Results

Position on Mask Use

Of the 600 tweets collected between June and August, 440 were pro-mask wearing, 134 were anti-mask wearing, and 26 did not declare a position. Pro-mask sentiment was most common in #WearaMask (99%) and #Mask4all (93%), while anti-mask sentiment was most common in #NoMask hashtag (77%). Pro-mask sentiment accounted for 81% of #Mask volume, while anti-mask accounted for 6%, and tweets containing no identifiable position accounted for 13%.

Evidence

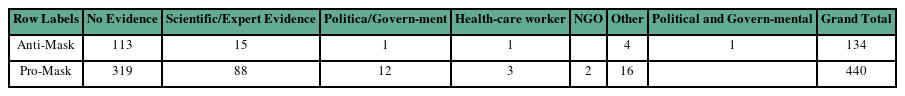

The occurrence of evidence as a justification for an individual’s position on mask use occurred at a rate of 24% or 143 tweets out of 600 tweets, with pro-mask tweets using evidence at a rate of 28%, while anti-mask tweets used evidence at a rate of 16%. The most common form of evidence used was from academic or scientific sources (71% of all tweets containing evidence), followed by “Other” sources (14%). Notably, in cases where evidence was used to justify the position on mask use, scientific evidence rates among anti-mask tweets were similar (71%) to pro-mask tweets (73%).

Study finds that public mask wearing stops spread of #Covid19. "The decreased transmissibility could substantially reduce the death toll and economic impact while the cost of the intervention is low." #Masks #FaceMasks #NoMasks #Coronavirus

Motivation

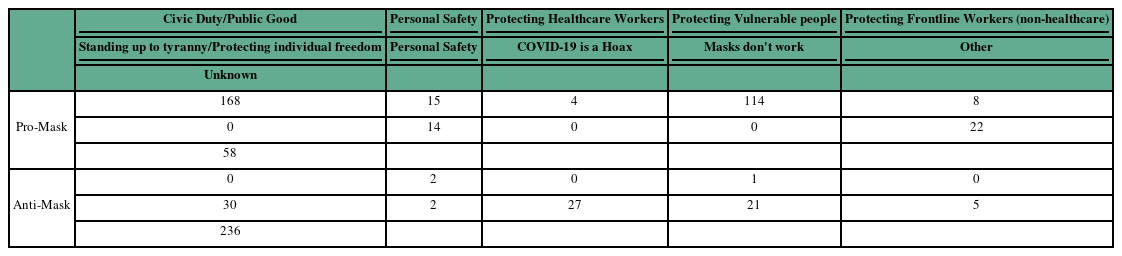

The most common motivations for a pro-mask position were: Mask-wearing as a Civic duty/Collective action (168), Mask-wearing as personal safety (15), and Mask-wearing to protect vulnerable people i.e. children or the elderly (14). The below example was coded as motivated by civic duty and personal safety.

Remember, rural counties, you are NOT safe from #coronavirus if there is a highway, train station, airport, taxicabs or even hiking trails into your area. People transmit the virus without showing symptoms. YOU MUST PROTECT YOURSELF AND YOUR COMMUNITY. #WearAMask at minimum.

The most common motivation for an anti-mask position were: Standing up to government tyranny/protecting individual freedom (30), Coronavirus is a hoax (27), and Masks do not protect against Coronavirus (21). The below example’s position was coded as motivated as “Standing up to government tyranny/Protecting individual freedom”.

Don’t tell me what to do, where to go, where to stand, what to wear, what to think, when to clap, what to fear. What’s my name? Read it out loud. #NoMasks

Trust/Distrust of Institutions

There were 201 tweets that expressed trust in institutions, 97% of which were anti-mask. Of these 201 tweets, 53% contained evidence, and 62% had “Civic duty/Public Good” as their motivation. In 100% of cases where the tweet was trusting of institutions but anti-mask (5 out of 201), expert/scientific evidence was used to align the anti-mask position with scientific consensus (see below).

The CDC just reported that the chance of dying is 0.04%. Please fight for our children to live their lives without fear from a virus that has a 98% recovery rate. #NoMasks #NoSocialDistancing #NoCV19Vaccine The social implications of these will harm our children.

There were 68 tweets that expressed distrust in institutions, 97% of which were anti-mask, 44% mentioned a conspiracy theory while only 18% used evidence to support their position.

The most prevalent motivations for the anti-mask position among distrusting individuals were: Coronavirus is a hoax (31%), Standing up to government tyranny/protecting individual freedom (28%), Masks don’t work (15%). 25 out of the 66 tweets (38%) which were anti-mask and expressed distrust in institutions attempted to debunk pro-mask positions (see below for an example).

Masks are USELESS. Look at this, people distanced and masked and yet supposed “cases” Masks are not giving us freedom, they are another step in this government Chinese police state plan. #NoMasks https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2020/aug/13/uk-coronavirus-live-news-covid-19-latest-updates

Counter-tweeting

There were several instances of tweets using a hashtag that was oppositional to the stated position of the tweet.

#NoMasks – Is it SUCH an imposition to tell people to wear a mask … that could save their life or the life of another? If you think this is so awful, maybe have a think about it.

There were 31 cases of counter-tweeting from pro-mask individuals using an anti-mask hashtag, accounting for 21% of all #NoMask tweets, whereas there were only 10 cases where anti-mask individuals used a pro-mask hashtag, accounting for 3% of all #Wearamask and #Mask4all tweets. 23% (7 out of 31) of pro-mask counter-tweeting used evidence to justify their position and 5 (16%) used personal appeals. Comparatively, 40% of anti-mask tweets (4 out of 10) used evidence to justify their position but none used person appeals.

Call to action

The most common call to action was “Wear a mask’” (75% or 390 out of 520), followed by “Don’t wear a mask” (25% or 129 out of 520), and political calls to action (8%). Rates of tweets containing calls to action were similar for pro-mask (89%) and anti-mask (96%) positions. Interestingly, pro-mask tweets’ rate of political calls to action was significantly lower than those of anti-mask tweets, with 4% and 17% respectively.

117 Californians DIED TODAY, And. @MikeGarcia2020. Doesn't. CARE. #CaliforniaCOVID19SURGE VOTE @ChristyforCA25, like your LIFE depends on it. #WearAMask #YourActionsSaveLives

Discussion

This study sought to understand the public sentiment around mask-wearing, the motivations behind beliefs and perceptions of this important and contentious public health intervention, and the rhetorical strategies and framing used by those expressing their stance on Twitter. By analyzing four prominent mask-related hashtags, this study found that anti- and pro-mask sentiments appear to be based on a range of motivations and expressions of these sentiments revealed a variety of themes, worldviews, and apparent rationales. This is consistent with the idea that changing health-related beliefs and behavior is difficult, and that interventions and public health messaging must account for the complexity of the social, political, and economic factors which influence belief and behavior. Our analysis attempts to not simply provide a snapshot of mask-related beliefs, but to unpack these complexities in the hopes of better understanding some of the dynamics that shape public sentiment about public health interventions, and the ways in which people communicate these sentiments.

The following sections propose some of the possible implications and opportunities for future research.

The political valence of anti-mask beliefs, and the presence of conspiracy theories

The rate of political calls to action was significantly higher for anti-mask tweets compared to pro-mask tweets, at 20% compared to 4% respectively. Our analysis also found a much higher prevalence of conspiracy theories in anti-mask Tweets.

News accounts and public polling have suggested that there is a strong link between political affiliation and beliefs and mask sentiment. A Pew Research Center poll, for example, found that in the U.S. Democrats were more likely to say they wear masks than Republicans (Alberga et al., 2020; Pew, 2020).

It is important to note that this relationship between politics and stance on mask-wearing appears to vary in different parts of the world. For example, one study found that most Canadians, regardless of political affiliation, demonstrated similar levels of compliance with emergency orders (Pickup et al., 2020). Yet as one of the authors of that study noted in a later article, perceptions of the threat posed by COVID-19 and the effectiveness of the government response did seem to be affected by partisanship, and perhaps more worryingly, in the time since the study was published there have been “signs of partisan splintering” (van der Linden, 2020). As the pandemic and the emergency measures designed to contain it continued through the summer and into the fall, “clear differences between left- and right-wing Canadians in terms of mask usage” began to emerge. Among left-wing Canadians, 94 percent reported adopting masks as part of their routine, compared to 68 percent of right-wing respondents. Supporters of the right-wing Conservative party are also more likely to subscribe to conspiracy theories about the virus (van der Linden, 2020).

Our analysis of mask-related Tweets did not include an explicit identification of political affiliation; Tweets were collected based on the presence of specific hashtags, and as such many did not include overt or implicit statements about political beliefs. However, the political calls to action present in anti-mask Tweets typically included statements of opposition to the Democratic party, or support for former U.S. President Donald Trump and positions that have been associated with the right-wing in the U.S.

Evidence type and motivation behind beliefs

Pro-mask tweets drew on evidence at a higher rate than anti-mask tweets (28% and 15%, respectively). Academic or scientific sources represented the most common form of evidence used, at 73% of all tweets containing evidence.

Earlier models of science communication largely focused on the flow of information, whereas more recent models also consider factors that shape and influence responses to information (Seethaler et al., 2019; Simis et al., 2016). Health agencies around the world are increasingly adopting a more nuanced understanding of communication, belief, and behavior change; for example, in its strategic communications framework, the World Health Organization describes how social norms can “make it easier or harder for audiences to adopt recommended health actions and policies” (WHO, 2017). This study supports the idea that scientific (mis)understandings cannot be distilled to whether someone is exposed to accurate or inaccurate information. Our data on evidence type and motivation behind beliefs suggests that anti-maskers are not primarily interpreting the scientific evidence incorrectly, or that they are not being exposed to the “correct” information. Rather, the most common motivation for an anti-mask position was standing up to perceived government tyranny or protecting individual freedoms.

Other common motivations for an anti-mask position included the belief that COVID-19 is a “hoax” or that the threat is overexaggerated, and that masks do not protect against the virus. Yet many of these same tweets also appeared to contain political motivations or statements that supported stances taken by former U.S. President Donald Trump and other right-wing political figures, such as former leader of Canada's Conservative party Andrew Scheer. This included, for example, concerns about the accuracy of data from the World Health Organization or claims that the organization helped China “cover up” the severity of COVID-19 early in the pandemic.

(Dis)trust in institutions

Trust or distrust in institutions was strongly linked to support or opposition to mask-wearing, with an overwhelming majority of “trusting” tweets containing pro-mask sentiment (97%). Out of the tweets that expressed distrust in institutions, 97% were anti-mask, and almost half of these tweets mentioned a conspiracy theory. Out of the entire dataset, only five tweets were both trusting of institutions and had an anti-mask position. In all five of these tweets, there was an attempt to align the anti-mask position with the scientific consensus, for example by claiming that there was scientific evidence that masks are ineffective at preventing the spread of COVID-19.

The practical implications of this study include supporting the importance of institutional trust in public beliefs and behaviors, and the fact that health messaging should address trust gaps. In these cases it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether a tweet is intentionally spreading misinformation and attempting to misrepresent scientific evidence, or if the author genuinely misunderstood the scientific consensus on mask wearing and COVID-19. If these authors are misinformed, it is possible that such misunderstandings could be readily corrected through the provision of accurate information. Yet it is notable that such instances – where the Tweet drew on a mistaken understanding of scientific evidence to support an anti-mask position – made up such a small portion of the dataset, again supporting the idea that public health messaging should attempt to address factors such as trust gaps rather than knowledge deficits.

Indeed, our findings are in line with previous research that has emphasized the importance of understanding the role of trust and its components in public beliefs and behaviors (Quinn et al., 2013; Udow-Philips & Lantz, 2020). The theoretical implications of this study include supporting the idea that communication strategies should include efforts to increase message credibility. In practical terms this might be achieved by encouraging “trusted influencers and messengers” to act as models and champions for the desired behaviors, or creating messages that highlight how the behavior is supported by communities, organizations, and peers (WHO, 2017).

Conclusion

As the COVID-19 crisis and opposition to public health interventions continue to develop, mask-wearing will likely persist as an important and contentious issue throughout the pandemic. Non-pharmaceutical interventions provide simple and low-cost ways of reducing the transmission of communicable diseases, and thus understanding public sentiment could help the uptake of these kinds of interventions and inform the development of public health messaging (Teasdale et al., 2014). Social media platforms such as Twitter play a role in shaping public perceptions of health issues and the spread of misinformation and also provide insight into public beliefs.

A limitation of this study was the number of Tweets (600) analyzed. The method of manually reviewing Tweets ensured that the inaccuracies of automated sentiment analysis were avoided; labeling tweets with an emotion remains a subjective task due to factors such as sarcasm, slang, or ambiguous use of emojis (Chapman et al., 2018). However, this limited the volume of Tweets that could be examined. Future research could attempt to validate these findings using automated sentiment analysis tools.

Despite the promise of social media to provide spaces for education, community building, and protest, the framing of issues on sites like Twitter can be constrained by "institutional norms, local politics, and contextual realities” (Ofori-Parku & Moscato, 2018). Other researchers have used the term “hybrid media event” to describe the “complex intermedia dynamic” between social media, the news, and other actors and platforms (Sumiala et al., 2016; also see: Vaccari et al., 2015). Drawing on this, future research could explore public sentiment around mask-wearing as a hybrid media event: geotagged tweets could be collected and then analyzed alongside local news coverage, bylaws, and public health statements to understand the interplay between these different actors and channels.

Other areas of future research include exploring other time periods of the pandemic beyond the early months examined here. Other research could explore mask-wearing as an expression of identity, or as a rapidly developing social norm. Earlier in the summer, pro-mask Twitter users reportedly “hijacked” anti-mask hashtags such as #NoMaskSelfie (Petter, 2020), a practice known as counter-tweeting – using a hashtag in a way that is oppositional to its intended meaning. However, there has been debate around whether this practice resulted in greater outreach for pro-mask messages, or if this actually boosted the anti-mask movement by amplifying their message and raising the profile of the hashtag, and potentially introducing more people to conspiracy theories (Dotto & Morrish, 2020).

This study has unpacked some of the apparent motivations, themes, and appeals used by people tweeting pro- and anti-mask messages, providing a starting point for exploring this phenomenon in future research.